Dragging my feet like a reluctant school child. I’ve been on the verge of writing so many times and yet prioritized everything above this task. It’s a fear of mine – deep and dark and quiet, cruel and steady, so casual in it’s proliferation – apathy.

I dread apathy. I fear complacency. I feel compelled to guard against it. I sometimes feel the righteous burn of wanting to rid it from those around me who weakly concede “but that’s how the system works,” or “that’s just how it is.” We lack imagination and ambition with that line of thinking and I can’t help but feel the deep need to build on the legacy of what has got us this far: the vision, bravery and fortitude to do something new, something better.

Occasionally I come across a play which is so urgently shouting it’s lineage and credentials, that I am forced to step back. Rocked back in my heels at the sheer weighty tidal wave of effusive significance or pedigree or accolades.

Such things always gives me cause to pause.

Mojo by Jez Butterworth is one such occasion.

Mathematically this production should add up. Talented director, talented designers, talented cast, hot zeitgeist aesthetic. But really there was something lacking.

Sitting there waiting to be transported or transformed I felt myself detaching from the world in front of me. Sitting aloof and indifferent – at best thinking “clearly there was no need for women in the 1950s in England” at worse thinking “why am I watching this? What is this saying to me?”

In 1995 when Mojo first stumbled across a stage in its first trembling steps, the neo nihilism of grunge was sweeping the world. The utopia of the previous generations offering love and peace was an empty promise and the resulting cynicism left those in its wake seeking numbness. Since then, candy-coloured pop music film clips have sought to compensate – offering Katy Perry and cheesy glamour as the antedote to contemporary western culture’s symptomatic depression. But in the 90s, the 50s cool was still keeping on – the legacy of James Dean, Happy Days, Grease – easy and familiar silhouettes on youthful memory. Cool was everything. Still is. So not surprising the clash of the above ground and the underground was such fertile soil for so many. I think about the context – beyond the particular playwright – into the large narrative of time and culture what this contribution means.

Perhaps what has happened in my reading of this play – in my context here and now – I’ve seen, read too much and so the naive unselfconscious ramblings of the boys in Mojo appear to be derivative (even if it did precede the flood gates of homage, retro 50s fascination). Referring to Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction… or any Jacobean tragedy or series of Channel 9’s Underbelly.

What I found most difficult about this play is how little I cared for or about the characters, their fate, their past – the story.

When I don’t care, I find it hard to share. When it’s hard to share, I don’t want to write about it.

And that inaction nearly destroys me. And so I write. Write something. Anything. Just to prove that I’ve not been beaten by apathy or complacency.

Written for www.australianstage.com.au

It’s dripping with Retro chic in every way possible. Sydney Theatre Company’s latest Wharf 1 offering has rockabilly, hipster fanfare written all over it: the promise of a 1950s rock and roll, dark gritty underbelly time capsule. An edgy feast for those hooked on the heavy thud of booted bovver boys, or so the Artistic Director’s note and the Director’s note suggest.

However Jez Butterworth’s Mojo is not delicately laced with the quaint tinge of nostalgia that retro acts of art can bring a contemporary audience, but drenched in design and nearly pulled under in the near two decades of gang/drug/thriller genre-content offered since its premiere in 1995.

The premise hangs on the fate of a single character “Silver Johnny” and the den of corruption and desperation that seeks to control his unstoppable talent. In the wake of real-life pop-star scandal (Justin Beiber, One Direction, Elvis Presley) and the subsequent spread of film, TV and gaming media geared to the underbelly or ganglands of other places/other times. This is a fairly familiar tale, told by Butterworth in a fairly unsurprising manner.

Though dutifully and deftly delivered by a very capable cast – Jeremy Davidson, Eamon Farren, Josh McConville, Lindsay Farris, Ben O’Toole, Tony Martin – and underscored by the musical ruptures of Alon Ilsar and Paul Kilpinen – Mojo falls short of the explosive and effusive praise quoted in the program.

Iain Sinclair with an all-star team of Pip Runciman (Set Design), David Fleischer (costume design), Nicholas Rayment (Lighting design) and Steve Francis (Sound Design) has produced a handsome and technically coherent piece of stage work. But the play’s the thing. And it failed to inspire or intrigue.

Running at two hours and thirty minutes, including interval, it runs for about as long as Quentin Tarrantino’s Pulp Fiction’s theatrical release (which was released a year earlier in 1994) without much of the glamour, humour, quirk, craft or curiousness. The story unwinds in a simple and unambiguous, linear fashion collecting moments of individual revelation from each character. The affect is an inordinate amount of steaming, stamping, brotherly drug taking, sexually ambiguous threats, some stale cake, some powerful guitar and a couple of bloodied garbage bins.

To what end? Is this a portrait of another time – to be regarded with the reverence of ages past? Is this an attempt to show the downfall of drug taking? Or the downfall of joining a gang or a band? Is this proof that men are essentially self destructive? Is this story to show the latent power of the next generation? And what do we learn?

It appears that the retro chic design of this production, fails to elevate the play above the resulting onslaught of like-genre parables of boys behaving badly.

]]>

As a teenage girl, Kafka’s A Hunger Artist was a story I read and re-read. This would only seem strange, I suppose, if it was true that Teenagers are NOT the most philosophical (and existentially angsty) humans on earth… and if I didn’t grow up in a small town which I despised for being small and a town. Reading was a consolation. Reading Kafka even more so. I could have spent a lot more of my time flirting with and then dodging teenage pregnancy, but instead I was reading A Hunger Artist, and thinking about the tragic cruel truth behind Kafka’s portrait of the fickle, skeptical general public. If you wasted your childhood in more interesting/sexy ways, perhaps you’d like to read the story here: https://records.viu.ca/~Johnstoi/kafka/hungerartist.htm

(Though NOT reading it will in no way prevent your curiosity in Clockfire Theatre Company’s latest offering: A Hunger Suite)

The story is summarized thus:

“The protagonist, a hunger artist who experiences the decline in appreciation of his craft, is an archetypical creation of Kafka: an individual marginalized and victimized by society at large.”

Taking this story as a departure point, Clockfire Theatre Company has investigated and re-presented the notion of the rejected artist in a surprising way – a series of scenes, images and chapters brimming with effort, with desperation, with humour and charm which captures attention and wears out its welcome into an absurd spiral of fatigue and pathos: a desperate hunt for validation, for attention or recognition.

Presented in the Old 505 Theatre – in my opinion, the venue in Sydney currently boasting the most exciting, innovative, interesting and challenging independent program – I was lucky enough to witness the first draft of this work in 2012, a bizarre and surprising patchwork. This was a draft before director Russell Cheek offered his eye, intellect and aesthetic to the project… before a composer and musician Ben Pierpoint gave breath to a bouncing bassoon… before a residency in Istanbul solidified and clarified the story, the feeling, the overarching look and feel of the production.

The result is not so much a linear story – after all this work is about performance, not about literature – it is about sensation. Using the audience as implied antagonists, the story reaches into the audience to fatigue us, to ask us to be fascinated, then bored, then disengaged. The effort which is squeezed out of the performers takes us on a parallel journey into the narrative. Performed & created by Emily Ayoub & Mine Cerci, through out the course of the evening we are directly spoken to, profusely thanked, tap danced at, asked to accept the transformation of person into horse, into limbless Cartesian horror. It’s strange, strange making and surprising. Echoing afterwards is the residual poignancy of the performer… discarded by the public. Forgotten. Useless. Rubbish.

This is difficult, beautiful performance. Abstract, beguiling and hilarious.

And if you see it, you’ll know I am right.

If you don’t go see it, it means Kafka was right.

Either way, I’m satisfied.

A Hunger Suite

Presented by Clockfire Theatre Company

http://www.clockfiretheatre.com/#!a-hunger-suite/cc5y

Performed & created by Emily Ayoub & Mine Cerci

Directed by Russell Cheek

Music by Ben Pierpoint

Old 505 Theatre, 505/342 Elizabeth St, Surry Hills

7-25th May 2014

Times: 8pm Wed-Sat, 7pm Sun

Doors: open 1/2 hour prior to performance start time

Tickets: $28/$18

The risks are great – not counting the obvious financial risk which touches all artists – new work takes a bit of hustling. It takes convincing of actors (and their agents), venues, audiences to invest time, energy and attention in something untested, unknown. When I am watching a new play – particularly in the independent sector – I consider that the actors must believe in the fundamental message, style of the play. I see the actor as an important participant in the curation and development of culture, ideas and I hold them accountable for their choice to be involved. The actor’s contribution is huge – and signals to me their values as a person and an artist in their support of the writer and director. The act of anyone committing their time and attention to a new work is an act of faith – an act of hope some might say – in the possible.

However, it can happen that what is generated can not and does not reach beyond the aspiration of moving the artform forward, or touching an audience. There’s the possibility that the production falls short, confuses, bores, baffles, exhausts, disengages.

The Australian contemporary playwright has a lot to contend with:

The history of theatre

An international pallet of performance styles

A huge back catalogue of great plays

Film

Literature

Interesting dinner conversation

International contemporary playwrights

Fads, developments and fashion in playwriting as a contemporary practice

YouTube

The Internet

Facebook and other social media

A literate, mobile, educated audience

Limited production resource

Differing performance styles, interests and experience of your cast

The physical limitations of the performance venue you are working in

As such the content, form, style has to be coherent, well thought out, well considered, timely, innovative, fascinating.

If the play is written in a series of re-enactments – without exposing the current issue, the audience is disconnected from the present, the work is not urgent and so meanders. If the characters are written to caricature or type, the audience has little to discover beyond cliche. If the mechanics of the play, for example stage management or set changes are brought into the play – it must serve the story, the theme or the message – otherwise it will appear gratuitous. If the characters tell the audience their inner psychology or expose their motivation which is in clear alignment with their action: the audience has no reason to lean into the play and discover anything for themselves. If the audience becomes aware of a change in lighting state, it is often to indicate a change in scene, mood or idea – if the lighting state does this without a thematic or structural change – or even to express a time of day, it disturbs the audience, without any pay off. If the character is established as angry and didactic at the top of each scene, there is little opportunity for the character to develop. If there is a character that is constantly making jokes or commenting on another character’s vulnerable reveal, or on an important monologue which is there to serve to cohesively bring all aspects of the story together: the audience can become distracted by the commentary, and not pay attention, nor give much weight to the message. The premise is everything. The characters status is important – shifts in status must serve the story, the message. Likewise a change in furniture must serve the story, or the space: remove a chair and you change the world. Is it true that a police officer or sargeant has infinite time to hear the self-aware, self-reflective memories of a criminal? Grant a prisoner freedom to walk out and get a cup of tea, and the premise of the scene is no longer respected as holding any gravitas. Tell the audience what the play is trying to say, eg “There is always hope” and they’re less likely to believe it, than if they were to walk away thinking and feeling there is always hope.

Additionally the question needs to be asked: if your question or premise of your play is, for example “is evil created or is evil innate?” – it might be worth considering if that is what your play is about. If perhaps your play is not about that, but about hope, it how important it is for the audience to know the conclusion of such a discussion “There is always hope” before they’ve seen the play?

Amanda is a play which requires some rigorous re-drafting, reconceptualizing if it is to overwhelm and bypass stories (plays and films and novels) which touch on similar themes in the cannon eg: No Exit, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, Wolf Lullaby, Hedda Gabler.

Amanda

written and directed by Mark Langham

performed by Amylea Griffin, Paul Armstrong, Elizabeth Macgregor

“”What did you do?” Was Amanda born this way or has circumstance made her what she is? What is she and, where is she? A new play from this multi award winning writer tells of our disconnection from each other, the ease with which we distance ourselves from others and much more. It does it with this writer’s customary wit and directness and is so sharp it may cut.”

May 13~18, 2014

Downstairs Theatre, TAP Gallery

Shag pile, shag pile everywhere – even climbing up the walls.

And just as well, too. I need somewhere soft to lean into, while sitting in the dark breathing in the words of Declan Greene’s Max Afford Playwright’s Award winning play premiering at Griffin Theatre Company – the provocatively titled “Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography.”

The Internet.

The latest in a string of many human lead historic revolutions – following the mechanical and the sexual – to improve and yet collapse the world as we knew it in the same moment. A place where Avenue Q exclaimed (and we’ve been chanting ever since) “The Internet is for Porn.”

It has be come the most powerful double edged sword for priviledged societies – presenting both democratization of information and prevalence of bullying, access and anonymity for individuals to provide, explore or share all corners of one’s thinking, personality, opinion, persona. The internet has made us clever quick at finding answers and yet lazy in our research and recall. The internet has provided a place for people to lance their emotional boils in chat rooms, in comments on social media sites. It has created a mighty swirling archive of grand human endeavour, curiosity and pettiness. The Internet has opened up a flood of thinking – good, bad and ugly- from across the globe (except maybe China) and has encouraged people to actively participate in its creation, maintenance and curation. It has made readily available some of the most astonishing moments of human interaction, linguistic disintegration/creation and crowd thinking…

The Internet is a huge, wild, restless Leviathan which saves and destroys with each key stroke.

The Internet is, really, in essence, the harnessing of human kind in all shades of emotion, thought and action.

That is what makes it so terrifying.

What makes it so terrifying is that we make the content and the content is shaping us… No doubt you’ve seen Gary Turk’s call to “Look Up”?

Declan Greene’s play is a portrait of the resulting effects of the internet: where there is access open to compulsive spending and obsessive lust…

The blurb goes like this:

“They met online. She’s a nurse in her forties, brats for kids, trapped in a loop of catastrophic debt. He’s in IT, miserably married and trapped in his own loop of nightly porn-trawling. Both of them crave something else – but not necessarily each other.

Take the plunge into the Too-Much-Information Age. Funny and fiercely written, Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography is a deceptively compassionate cringe-comedy of mid-life loneliness, hidden zip folders and barely concealed desperation.”

Declan Greene’s Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography is a brutal spectacle exposing extreme human gluttony as a defense mechanism against disconnection, loneliness and frailty.

Here he exposes all too familiar shame and guilt and impotence of modern life – the secrets we keep that gnaw and erode.

Life full of compulsive spluttering lust and urgent frivolous material acquisition.

And it left me reeling in a car crash hypnosis…

In an interview conducted by Elissa Blake the headline states “Playwright Declan Greene says Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography isn’t repulsive.”

And I would agree by adding…”Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography isn’t repulsive any more than the uttering of a painful truth or the revelation of shame or trembling lost vulnerability is.”

Ideas expressed through the flesh of two actors, Steve Rodgers and Andrea Gibbs, the direct address places the audience as possible love interest, best friend, counsellor or confidant – they switch between story teller and enactment as swiftly as the mood shifts and changes. The writing is fragmented – sliced up into fourteen scenes.

The designers – Marg Horwell (responsible for Shag pile and costume), Matthew Marshall (light) and Rachael Dease (Composer) – work within Lee Lewis’ muscular direction – keeping bright and ready a darker moment in the story and sugarcoating reality.

However, some aspects of the direct address push me away, asking me to observe a reflection or rumination or realisation – instead of asking me to connect directly to action unfolding and by that I mean inviting me to “lean in.” The affect is ultimately one of an intellectual exercise of understanding and weighing what I’m told with what I assume or already know. The moments which swept me up and away were predominantly watching Rogers react to Gibbs contrasting to the dialogue spoken because I felt I was working harder to find the truth- not being told it plainly.

There is a value in taboo, in speaking the unspeakable – and though these topics and revelations have been covered in literature, in newsprint and in online forums – hardly are these confessions spoken publicly. What must be congratulated is the work of both Declan Greene and Lee Lewis to expose and present this contemporary crisis we are experiencing where we sabotage and self-harm through secrecy or through gluttonous excess. We are ultimately the ones who will bring about our own downfall – and that message has often been told. What is interesting is the possibility that we might also be the answer to our own salvation as we catch our reflection in the blade of a double-edged sword.

BOOK

Phone 02 9361 3817

Online http://www.griffintheatre.com.au/whats-on/eight-gigabytes-of-hardcore-pornography/

PERFORMANCE DATES

Previews 2, 3, 5, 6 May

Season 9 May – 14 June

Subscriber Q&A after the performance on 20 May

PERFORMANCE TIMES

Monday – Friday 7pm

Saturday 2pm and 7pm

RUNNING TIME

Approximately 90 minutes with no interval

VENUE

SBW Stables Theatre

10 Nimrod Street

Kings Cross NSW 2011

It is rare that I’ll venture from the word-heavy comfort of my true love (text-based theatre) and meander into the muscular flesh-fest of contemporary dance… but I do from time to time. This special occasion is a triptych presented by Sydney Dance Company in their 45th Anniversary Year – two new works and a remounted work from yesteryear.

Not practiced in the language of (nor the world of) dance, I feel fairly limited in my ability to articulate the specific thoughts and experience of watching phrase upon phrase of movement. I watch trying to form a sense of how to articulate a moment or an image – and so watching becomes in part an exercise in writerly craft -a previous example of trying to write about dance (Specifically a SDC show) can be found here: https://classic.augustasupple.com/2012/03/2-one-another-sydney-dance-company/ . To build my dance articulation muscle I’ll continue to exercise because I am not yet sophisticated in my viewing, nor in my language in responding or reviewing dance.

Lucky the Sydney Dance Company is so robust in it’s history and vision, that the likes of a reader and writer like myself could not possibly dint their reputation as I fumble about in the top drawer of my language skills to find something coherent to say. It’s taken me too long to pluck the courage up to say something… but now at least I have.

Just in time for the show to move on from Sydney to a bright horizon.

The difficulty I had with this work is that I felt nothing but curiosity for the unfolding of events. I’m not quite developed yet to hook into movement over text when text is presented (such as in L’Chaim), or in movement over music (such as in 2 in D Minor), or to privilege movement over lighting design (as in Raw Models) – and I think my review reveals that. Unfortunately I found the last piece tragic – not comic – and especially brutal in that the simplistic line of questioning of dancers returned fairly basic articulations of why they dance and what they like about it. It deflated me the mechanical and glib responses. I do wonder if I’d come to that piece without the baggage of knowing much of Zoe Coombs Marr’s recent work with “post” (eg Oedipus Schmedepus, Who’s the Best, Horses Mouth Etc) if I’d view the work differently. Perhaps.

Written for www.australianstage.com.au

A black space, a white screen hangs above. Four white illuminated lines form a frame. A violinist takes her place. From the darkness, light: a melodic weaving, the climb and fall of scales as they slide and melt. Precise and agile, a body moves, reacting, resonating with formal elegance, partners with another body creating physical echoes of JS Bach’s Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor.

In Rafael Bonachela’s latest work 2 in D Minor, the tradition of Bach’s intricate and restless melodic themes is transposed into the dancer’s body in a display of aristocratic maximalism. A suite of actions provides a physical “response” to the violinist’s “call.” Technically crisp and clear, movements responding to individual dancers personal experiences are repeated to a point of visual exhaustion. Bonachela’s note on choreography and costume collides with the experience in an unfavourable way. The intent on a non-gender specific costume leans into the masculine form, denying a connection of the personal or feminine within the female performers. Experience is translated into expression, but abstracted into uniformity in the process, presenting not a unique and individualistic emotional experience, but a homogenization. Movements are measured – not built upon in pace or intensity, but to the degree that exact repetition is it’s own reward. Each suite of Bach’s Violin Partita No. 2 in D Minor is punctuated with fierce and fizzing “sound clouds” composed by Nick Wales, creating an abstract response to Bach’s neat structure. This punctuation extends the conversation between music and movement, ultimately lifting the work out like an spiral of fibonacci numbers, from the expected and the usual, climbing steadily and barely resting.

Restlessness might be an underlying theme or modus operandi within The Sydney Dance Company – commissioning eight new works to celebrate their 45th Anniversary – two of which appear in Interplay’s triptych – 2 in D Minor choreographed by Bonachela and L’Chaim! choreographed by Gideon Obarzanek.

The second piece in the evening’s program is a revistation by Jacopo Godani’s critically acclaimed 2011 work Raw Models. A heavy, pulsating, portrait fuelled by animalistic urgency, sexual power and primitive survival, Raw Models is a muscular intense exploration of the natural versus the constructed in human motivation. Dark, sensual and unyielding, Godani’s work combined regimented action with moments of lithe and heated confrontation. Music by 48nord (Ulrich Müller und Siegfried Rössert) is a blend of electronic sounds, instrumentation filtered, mixed, layered and transformed into a composition which according to their program note “would not be possible to do live.” Atmospheres punctuated by shadows and hiccups of brilliant light, this work is undeniably powerful, eye-catching and relentless.

Lastly, Gideon Obarzanek’s L’Chaim! offers a completely different experience. Although using a lighter palette of colour, sound and text, the overall affect is equally as dark and considered as the previous instalments in Interplay. Music by composer Stefan Gregory builds from a place of repetition to an ecstatic burst of traditional dance. David Woods provides a line of textual interrogation performed by actor Zoe Coombs Marr asks questions of a philosophical nature about the very meaning and origin of dance practice, dance aesthetic and a dance career – an interrogation held whilst the company jump and jiggle in precise formation, a gruelling act of restless, visually exhausting movement, which though athletic and ordered ultimately presents the rudiments of dance at its most casual. This irreverent self-conscious jumble of caricatured tropes, glib responses, puns and brutal simplistic self reflection ultimately boils down to “joy.” However, is that meat enough in this particular tri-part presentation of “playfulness” or is it an easy pathway into popularity through being obvious? The weight of dance history, the skill and the tenuousness and fragility of the dancer is bludgeoned by text and cutesy gimmicks, leaving nothing but sour and simple taste in my mouth that dance is brutal, to subvert one’s artform into the obvious and entry level understanding of human existence is ultimately cruel and ungrateful, and perhaps that’s what artists ultimately are?

Interplay is an intriguing suite of works by Sydney Dance Company full of experimental expression, philosophical questioning and casual elegance. Each section offers an exploration into the body’s relationship to sound and space and offers much to chew over post-event.

.

******

Sydney Theatre

Preview: Saturday 15 March, 8pm

Opening: Monday 17 March, 8pm

Tuesday 18 March, 6.30pm

Wednesday 19 – Saturday 22 March, 8pm

Wednesday 26 – Saturday 29 March, 8pm

Tuesday 1 April, 6.30pm

Wednesday 2 – Saturday 5 April, 8pm

Matinee: Saturday 5 April, 2pm

Tickets $30-$75 (transaction fees apply)

Phone Sydney Theatre Box Office on: 02 9250 1999

Canberra Theatre Centre

Opening: Thursday 10 April, 7.30pm

Friday 11 & Saturday 12 April, 7.30pm

Tickets $30-$63 (transaction fees apply)

Phone Canberra Theatre Centre Box Office on: 02 6275 2700

Southbank Theatre, Melbourne

Preview: Wednesday 30 April, 8pm

Opening: Thursday 1 May, 8pm

Friday 2 – Saturday 3 May, 8pm

Wednesday 7 – Saturday 10 May, 8pm

Matinee: Saturday 10 May, 2pm

Tickets $30-$75 (transaction fees apply)

Phone Southbank Theatre Box Office on: 03 8688 0800

I have no doubt: the personal is political. But who are these “persons” making things of their own politics, and politics of their own person? If we are to examine closely: the politics of me, you, us – would any of us be able to guess how any of our personal politics could steer 90 minutes of entertainment?

The blurb goes a little bit along the lines of:

“Five contenders. Five rounds. You choose. Employing high octane performance and innovative hand-held voting technology, Fight Night is a playful and immersive night of theatre. While your vote may reflect the personalities on stage, the process will be just as revealing about yourself. How fast do you judge or condemn people? Based on what? In a society where beauty prevails and even the world of politics is not safe from the cult of celebrity, director Alexander Devriendt has created a clever political game, treading a fine line between democracy and the tyranny of majority.”

We meet our host. Introduces the devices in our hands, hanging on thick black lanyards around our necks. Introduces the technical crew. Introduces the premise. Introduces five hooded representatives. All caucasian. Tidy. Approachable. Generic. Each with their own appeal, or ability to repulse: visually, vocally, or through attitudes, perspectives or oratory style.

We are about to go through a series of questions about how we want to be represented and by whom – they answer questions, they are asked to speak to us knowing only a statistical figure about the group in the room.

(On opening night at the Sydney Theatre Company Wharf 2 space, we are: aged between 25-44, earning less than $35,000 a year, many of us are single, many are non-religious, many are a little bit racist, many are offended by specific words.)

It’s an interesting exercise on statistics and data collection – especially in this setting, a part of me would prefer to return to another venue or another night to compare reactions…. is the opening night crowd at the STC really that single? Are we really that wealthy? Are we really that mistrusting of the group? Are we really only mildly loyal to the actions of a representative we are loyal to?

I’m not really interested in spoiling the unfolding of our particular night of pushing buttons (and some of us had our political buttons pushed) – because the premise is really what is on show, not the writing or the performances. What is most important about this show is about the individual’s behaviour in response to the group assumption about the group’s behaviour. Is there a main theme? Perhaps. The most simplistic of readings shows how democracy (in at least an Australian context) is flawed.

Yes. I think we knew that.

The more interesting aspect of the show is the personal revelation of where one’s personal attitudinal, moral and ethical values are placed, especially when anonymous voting allows you to reveal where you fit in the spectrum of the room.

The active participation within the system of “Big Brother style” voting off – is, of course, voluntary. At no time are we forced to press a button. But we do. We engage with the format of the show. We are a part of the show’s structure. If we were not to participate there is no repercussion. Except perhaps the show being short or stuck or without significance. In Australia, with compulsory voting, we are well attuned to voting because we have to. A compulsion. Compulsory.

Hypothetical situations are posed. Questions of the audience flip between the general and the specific. For example,

“Which word to you find more offensive? Nigger, Faggot, Cunt, Retard, or none of those words.”

“Are you a little bit Racist, Sexist, Violent or none of these flaws?”

“Are you Religious, Spiritual or Neither?”

As someone who prefers “fair but indecisive” leadership when polled I stayed with the same candidate right to the end of the show. Which is remarkable as I was decisive about this action.

It is an interesting portrait of the political and attitudinal landscape, however as a piece of theatre or art, it lacks conflict, tension or dramatic action. The game changing moments aren’t surprising enough to raise the stakes and at a certain point of the structure – the final point to be made – the stakes aren’t raised sufficiently for us to do anything but to meekly and compliantly either sit in our seats, or quietly dwell in the foyer.

What if this show created an occasion of upheaval? Would the political structure be broken? Could theatre, specifically, could *this* particular piece of theatre change the world, not just represent the flaws of the system that we are already familiar with? Why are we watching it? Are any of us moved to action? Are any of us hope to change the course of the show: to really push the actors through their paces?

No. We are a dull and basic audience to this production, just as we are a dull and basic demographic voting for the latest rehearsed actor to perform the role of politician.

Our politicial system is ineffectual.

Theatre as an artform/agent of change is ineffectual.

We, as an audience, as a population – a majority with ideas, money, influence and community – are ineffectual.

We end as we begin, shrugging and complicit in how things are directed. We are responsible for our actions, their actions, and we despise the machine we feed, and feel powerless to create an alternative structure. And we all eventually walk downstairs.

I look out to the water of Sydney Harbour.

I drink wine.

I listen and engage as those around me remark on the gimmicks of the production.

I engage with the conversation.

I politely smile. (Meanwhile I feel empty, powerless and depressed.)

I don’t say I felt bored. I don’t admit to feeling restless.

I offer alternative dramatic solutions to the flat structure of the performance – not to anyone who could consider them as options.

I walk away.

I am as ineffectual in my theatrical engagement, as much as I am in my political viewpoint. Theatre as a system, mimics the system of politics. And I’m left high and dry.

Perhaps that’s the point.

CREATED BY: The Border Project and Ontroerend Goed

CAST: Sophie Cleary, Valentijn Dhaenens, David Heinrich, Angelo Tijssens, Roman Vaculik, Charlotte Vandermeersch

DIRECTOR: Alexander Devriendt

WHERE: Sydney Theatre Company, Wharf 2 Theatre, Hickson Road, The Rocks

WHEN: Thursday, 20 March 2014 – Sunday, 13 April 2014

TICKETS: $35 – $65 (+ booking fee). Box Office: 02 9250 1777

MORE INFO: http://www.sydneytheatre.com.au/whats-on/productions/2014/fight-night.aspx

Swathes of heavy cloth, canvas, or calico – the thick sails of a ship or the drop sheets in a house mid-renovation. Scuffed grey floor. Some chairs. Functional, nearly sculptural. A neutral zone for the scenes to smear and blend, I’ll know where I am because I’ll be shown or told through light or line or a hum of sound.

Human relationships are amongst the most intriguing examples of symbiosis. Sometimes a mutualism, sometimes commensalism, some times parasitism, humans just can’t seem to live without each other. At the very core or the start of this is the family. There’s no doubt families are difficult, essential, destructive, nurturing, loving, confronting, fascinating building blocks of any community. Family – the idea of, the actuality of – is inescapable. And the inherent conflict is this: the battle between the self/self-interest and the family unit/community interest.

The battle with oneself is hard enough, but to battle with oneself in the inescapable presence of family – the memory of, the reality of it, the expectation of it? The assumptions. The history. Generations colliding and asserting a world view which is nearly incomprehensible to the other. A negotiation between duty to self and duty to others is endless – and more pointed, more poignant in reference to those whom on we rely on, owe much to – family.

In a continuation of the Pantsguys juggernaut, On the Shore of the Wide World (the second play staged by this company written by Simon Stephens) has harnessed once again the impeccable Anthony Skuse, whose direction – firm, kind and clear – releases more than one would assume from this play. On face value the dialogue is fairly everyday – not overly heightened – no Patrick White Dream aesthetic, no epic Dorothy Hewitt politic. This is simple, plain English.

“Alex Holmes is ready for adulthood, ready to lose his virginity and ready to leave his home town. But history isn’t on his side. Alex’s parents Peter and Alice are careening towards infidelity after the impact of a recent tragedy, and his grandparents’ relationship continues to splinter. The sting of regret is turning out to be a Holmes family keepsake.”

Essentially this is a multi-generational family drama wherein the duty to self (desire, grief, love, freedom) collides with the duty to family (monogamy, stoicism, loyalty, security). Under Skuse’s calm eye and warm heart something more is found in this beyond the narrative of pain and death and fidelity. There is a genuine even weaving of the generations pain, fear, desire is equal but different. This is a simple story, beautifully told. But this is not just a coming of age story for Alex. No. It’s really the showing of how a family comes of age. Confronts and negotiates loss and desire, faces betrayal and blame.

In the director’s note, Skuse finds a commonality in three of Stephen’s plays in place and time – Stockport over a five year period – and posits that the question hidden within this triptych is:

“How is optimism possible in a world falling a part?”

Asking this question, demands a huge amount of optimism – based on a cynical premise. It demands compassion from all – each performer and character, each audience member needs to be willing to believe in redemption or loyalty… the essence of which is love.

And in this production it’s undeniable – the answer is – has and will be – love.

Love – as a conscious decision to forgive, to choose the other over oneself, to stay, to confront what is and has been. To move over and beyond self for another – wife, brother, lover, grandparent, parent, child…

What love looks like in this family is not righteous, nor bombastic. It is the quivering, quavering, trembling stubbornness that says “no, I need you…” or “I can’t let you…”

And that is remarkable.

A strong ensemble listens to each other with intent and focus: Alex Beauman, Paul Bertram, Kate Fitzpatrick, Huw Higginson, Graeme McRae, Lily Newbury-Freeman, Emma Palmer, Amanda Stephens-Lee, Alistair Wallace, Jacob Warner.

Scenes become observed, the characters listening to the story as though they carry the memory of each other, or the concern of the other with them, theatricalizing what could be a fairly pedestrian scene of the everyday. The difference is that Stephen’s has found the tenor of three generations, the timbre of their yearning and sustained it throughout the play. It’s a beautiful portrait of inescapably inter-linked lives.

The tension within each individual – between between yearning and regret, duty to self and duty to others stretches thin. Skuse’s production like a cool Summer breeze brushes over and through Stephen’s Aeolian harp – so soft, and natural and familiar. Like breath. Like love. Like family.

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,

Before high piled books, in charact’ry,

Hold like rich garners the full-ripen’d grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour!

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love!—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.

Read Diana Simmonds HERE

Read Brad Skye HERE

Read Jason Blake HERE

It’s taken me a while to actually write about this show. Several factors contributed to what can from all external evidence would suggest as a dragging of ones feet (pen?) – but it’s more like the cogs and the levers have been clamorous inside my head and heart about this piece – more so than I had anticipated straight after the show. My internal machine noisy.

So the biggest and saddest thought I’ve had, triggered by this production (and the effusive response to it which I feel compelled to list here: John McCallum and Jason Blake and Diana Simmonds )

So here’s the thought:

If we need old and classic texts to show us social issues that “haven’t changed” in hundreds or thousand of years in the telling… then the text has failed at its job: to incite revelation and revolution.

Classic plays are an indication that theatre fails.

And this thought has really been making me feel terribly glum. Really glum. And so I’ve been thinking about the Ok Radio session at the Australian Theatre Forum 2013 (read Jane Howard’s post and my post if you want to join in the thinking with me)

If the theatre (especially via a philosophical art movement like Expressionism) is an agent of social change or a catalyst, surely after 3000 years of practice we would have stamped out some of the more ugly human traits via a means of social evolution?

Thinking about Machinal – and what seems to be acknowledged how this is a neurotic woman’s story (which frankly I don’t read it as in this my current context) – I see this as a portrait of choices about accepting one’s jailer’s instructions. I read it as the cracking open of expectation and obedience.

But what is so amazing and irritating about this experience is that we sit there in the dark, our hands politely folded in our laps, obeying the laws and conventions of what it means to be watching theatre. We sit numbed and silenced in the darkness.

There is no revolution here.

I wonder if those that ache and itch to escape their jailers (mortages, marriages, debt, jobs) inspires the theatre goers who witness Machinal to emancipate themselves? Or are we so seduced by the delight of a night out and away from our usual context that it appears more as a singular blip on the radar?

Perhaps the power in this play can be found in this complacency. We observe it placidly (as we do with the world at large) unaware that we (as audience) are condoning and supporting in silence and inaction every act.

Perhaps the notion that this is a play about a woman (as opposed to a person) says more about the stale and confused values of us the audience (or producers or whomever) at large?

Perhaps the problem that people marry for money, and kill for the right to passion/romance/imagination is a universal and timeless one. And perhaps that is the horror of being human? And why do we observe these timeless acts? To reassure we are all in a rut together? To be reminded that this is how it has always been…

I’m disappointed in theatre right now.

I’m disappointed that these stories are being presented as “still relevant” and that we still do nothing as an audience to overhaul our philosophical aches.

So… you want to know did I enjoy the show? I did. But not in a smiley smug way… but in a “I’m thinking big thoughts and I can feel the cogs whirr… I am watching as I shift the rubicks cube around and around in my head…”

I am a machine that is part of the machine.

Written for www.australianstage.com.au

Five crisp boxes of light. We’re faced head on by an indicative army of office workers: grey suit pants. White shirts. Ties. Relentlessly click-clacking retractable pens as though the action was to perforate the air with visible punctuation. A man’s shadow in a brightly lit doorway announces an important arrival. A woman gingerly finds her way to her seat, to the job where she awaits an endless workload, interrogation and the grinning advances of a much older boss.

First produced on Broadway in America in 1928, Machinal by Sophie Treadwell is a piece of American expressionist theatre which follows the spiritual awakening of a young woman (Harriet Dyer) who is pushing against the established expectations of a emotionally mechanised society. An invalid mother (Wendy Strehlow) who encourages pragmatism over romance in her daughter’s pursuit of marriage, seals Helen’s trajectory in to a life of duty and compromise. Before long, Helen has married an affectionate and doting husband (Brandon Burke) whom she is repulsed by, and suffering from anxiety, dread and foreboding. A chance encounter at a bar finds her tumbled and tumbling around with a lover (Ivan Donato) a man with a dark past his conscience has been easily reconciled with.

Here at the Sydney Theatre Company, director Imara Savage has edited and transported the play into a contemporary “no-man’s land” harnessing the very simple chapters of an inevitable decent into a dark decision. The ensemble cast supporting the scenes (Matthew Backer, Katie McDonald, Terry Serio, Robert Alexander) create a kaleidoscopic world of monochromatic judgement. At each pivot point the surrounding context repositions our sympathies towards the young woman and we find ourselves siding with her plight.

Presented with one of the most inventive, spectacular and sculptural lighting designs (Verity Hampson)on a Sydney stage in some time, Savage has directed a fluid and well-crafted story. The light shifts in colour and shape and form with an angular intensity that both isolates and contains the performance. Here the light also becomes a character casting a judgement across the action: a winking glare from six fluorescent tubes, a series of rigid boxes, the pitch of the roof of the house, an electric chair glowing with righteous power.

Performances are taut and direct, Harriet Dyer finding an easy and charming childlike place balances the drudgery of duty as wife and unwilling mother, Brandon Burke slides easily into the skin of the smug and un-self aware husband. Ivan Donato pierces the production with all the confidence of a well-practiced philanderer. However, there is a very clear and unambiguous chord of intention and agenda coursing through this reading of the piece – at no time do we condemn the woman for her actions. Instead society is blamed – but we are not implicated in that blame we are instead silently nodding along with the choice. I am left considering what action Treadwell’s Machinal wants us (as the audience) to take? After nearly one hundred years of production, it is a frightening notion that the play is still “timely.”

This is an interesting portrait of a person, but a powerful exploration of personal choice in the face of wider societal expectations. Savage has nipped and tucked Treadwell’s play in a fierce light sabre cutting though a fairly dark view of social conditioning.

]]>

It took me some time to write about “The Godot” currently playing at the Sydney Theatre, produced by the Sydney Theatre Company. I knew that the delighted opening night foyer, the thunderous applause and the casting of two of Australia’s most accomplished celebrity theatre actors in the lead roles of Di-di and Go-go was a recipe for success. The desire to peck out a rapid-fire review was diminished: after all this play is about Waiting. Ruminating.

So I thought I’d follow its lead.

This is my fourth Godot.

I’m 34. I think there might be another 3 Godots to be seen in my lifetime. Perhaps when Toby Schmitz or Ewen Leslie find their whiskers greying and their middle-aged bellies paunching. (tres impossible!) But at the moment, I head the warning of the plays that keep popping up in my life – a kind of artistic/philosophical guidance that whispers “be careful what you wait for…” I must pay attention to it.

Godot 1.

Sydney University Dramatic Society (1998)

I walked out. It is one of the few plays/productions/presentations I have ever walked out of.

At the time I was an angry young woman (ask my classmates of those Halcyon days!) who’s temper was especially short before lunchtimes. It was a hot, languid day. Sitting in the dark cave of the Cellar Theatre. I was hungry. I stayed for Lucky’s speech – which was beautiful and possibly the best I’ve ever seen performed – and then left. I was alter told that me walking out was Beckett’s intent and I had played STRAIGHT into his clammy irish hands!

Godot 2

New Theatre’s production directed by Luke Rogers. I think this was in 2010? A very clear and visually crisp production. I recall Martin Kinnane’s lighting design being especially impressive. I had forgotten how obsessed with the prostate Beckett is in this play, until I saw this production.

Godot 3

The Godot that is known as “The Sir Ian McKellen Production.” Circa 2010. A grand affair. At the Sydney Opera House. I attended with Mr James Waites who loves this play (he claims it is his favourite play!) not just for its punning resonance. It was one of those light misty rain umbrella days. The theatre was warm. It was a dim-lit monochromal design. People gently snoozed through it. I sat alert and upright, not wanting to miss Mckellen. I was frightened of Pozzo, I remember that. It was a study of the vaudevillian Godot – of age and stamina.

Godot 4.

Something felt playful and open about this Godot. I loved the little carrots nibbled in the show. I loved the big arcing angle of Pozzo’s entrance. And you can read more below.

I know James Waites in particular loved this Godot. I know many people will and do.

The interesting thing with all ancient or classic texts – texts that have survived criticsm over a period of time and swathes of thinking – is that I sometimes stop examining the text. Lately – more than ever – I’ve started reading new productions of old plays with the same critical ear as that of a new play – not to assume it’s earned its literary stripes but to make sure the stripes aren’t fading under the harsh glare of time’s light and attention. Godot still is a rule breaking, audience provoking text. Though I can’t help but wonder if the diamond encrusted wrists clapping at the STC are clapping more the grand spectacle of celebrity, than the genius of writing at work?

This review was written for www.australianstage.com.au

A dark open mouth of a proscenium arch, hemmed with a moustache of broken, missing or faded light bulbs. A thin, endless branch arcs into the sky. Grey, brick-worked waste land. Two men, like tattered coats upon a sticks, wait.

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is perhaps one of the most intriguing examples of innovative playwriting of its time. Here, across the sea and across time, and culture and all the other identity defining hallmarks of art, Waiting for Godot finds itself at The Sydney Theatre, still waiting.

The premise is simple. Two men, Vladimir (Hugo Weaving) and Estragon (Richard Roxburgh) wait on a country road for Mr Godot. During this time their waiting is interrupted by minor squabbles, the desire to quell hunger, attempts to remember, attempts to reassure, attempts to entertain each other – attempts to test each other’s commitment to each one another, game playing, recitations, singing, a man with a whip known as Pozzo (Philip Quast) and his pale male servant Lucky (Luke Mullins), attempts to remember why and how they came there… an attempt to piece together a plan or a story or a history.

The experience of this play, as opposed to the reading of this play, one of the most meta-theatrical, self-aware acts of popular art. The audience, like Didi and Gogo, wait for something to happen, wait for someone else to decide their fate… and whilst waiting their time (and ours) is filled with actions and words. It is an ache of anticipation experienced by both characters and audience in real time.

And so to watch as these men at the mercy of another, as we are at the mercy of them – sitting as we do in the darkness, watching.

Weaving’s Vladimir is upright, articulate and grand in his broadness. Roxburgh’s Estragon is a small aching poet, finely sketched and crumpled. Mullin’s Lucky is filled with ghostly agony, red raw urgency and a vicious streak. And it is Quast as Pozzo who fills the stage with a mighty and impressive voice – the central sun around which Didi and Gogo orbit. It is in this Waiting for Godot we see the wide reaching universality of oppression, the surrender of control – the desire for control and to be controlled, the need for direction and for the obedience of others – for the complicity in the shape of our own destinies.

Director Andrew Upton has shaped a playful and fluid Waiting for Godot, assisted by Associate director Anna Lengyel. This play “written by an Irishman in France, in a production conceived by a Hungarian by directed by an Australian” has a distinctly universal feel – as absurdist theatre is designed to have. We are the everyman in the everywhere, feeling the weight of the nothingness.

Nick Schlieper’s lighting design melts the hard corners and angles of the set – the human shapes amongst the industrial rubble are warm. Subtle thrumming of sound by Max Lyandvert supports, but does not instruct nor obstruct the scene – instead it’s like the softest watercolour blue fading into white. All in all a symphony of design at work – costumes (Alice Babidge) slide neatly into the set (Zsolt Khell) and we watch. And wait.

There is pleasure in this waiting. Pleasure found in wildly spoken recitation, in the deep, round vowels of Philip Quast’s undeniable velvet voice. Pleasure in the familiar and complementary pairing of our dearly beloved Roxburgh and Weaving. Pleasure in all the moments to be found and paced with such loving care, by a caring directorial eye. Too easily Waiting for Godot can be a steely criticism on aging, on power, on pettiness – and in Upton’s production we feel as much as we think.

A rare balance is struck.

There is pleasure in the pain of waiting. Of speaking. Of deciding to relinquish all. Beautiful. Horrible. A terrible beauty has been born.

Sydney Theatre Company presents

WAITING FOR GODOT

by Samuel Beckett

Director Andrew Upton

Venue: Sydney Theatre, 22 Hickson Road, Walsh Bay

Dates: 12 November – 21 December 2013

Tickets: $55 – $105

Bookings: 02 9250 1777 | sydneytheatre.com.au

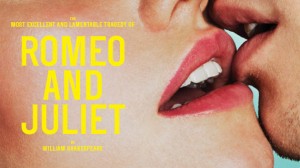

Romeo and Juliet – you know the blurb “The greatest love story of all time? Certainly. But it’s also a prototype for some of culture’s other great narratives: the rebellion against generations past, and the need to escape from a predetermined future. One of the most thrilling things about young love is that often it is forbidden. And that very act of prohibition makes it all the more alluring.”

And so when we know the story so well – the star crossed lovers who end up destroying their lives (and the lives of those around them) – that in the production it becomes more about the journey than the destination.

Here the journey is heart-thuddingly loud – but not through sexual tension or raw, urgent passion – but through the music pulsing through the speakers.

The most simple of heartbreaks can happen when one sees two people blindingly in love. It’s the stuff that keeps weddings wet-eyed. The joy of witnessing love (or lust) and the pain of remembering the disappointments love can offer – the compromises and the changes love makes in us all.

The play hangs upon the emotional temperature of the two lovers- if the temperature is tepid, the drive of the play becomes about facilitating the misguided, selfish, rebellious teenagers – not about ensuring that nothing gets in the way of true love. Perhaps this was director Kip Williams’ aim? To demonstrate the folly of young love? To show the stupidity of the friar (Mitchell Butel) and the Nurse (Julie Forsyth) in their facilitation of the union? To show the cruelty of the parents?

What I admired about the production was the comfortable, intelligent ease with which Juliet reasoned in regards to love (Eryn Jean Norvill) – she’s no giddy, silly girl, this Juliet. I also enjoyed the sweet and comfortable Benvolio ( Akos Armont – whom I fantasized was our love interest through much of this production) and the steely gaze of Anna Lise Philips as she swanned and swigged her way through a parade of feathers as Lady Capulet.

The cuts are many and varied, you can read across the reviews for responses to them:

The Australian HERE

The Daily Telegraph HERE

The Sydney Morning Herald HERE

Crikey HERE

In Kip Williams production, the drive of the play was about strategy more than sensuality. I began to realise that the truly physical embodiment of male sexuality did not sit within the bones and flesh of Romeo – but of Mercutio (Eamon Farren – humping most things and people in sight) – and that the sexual rebellion of Juliet was really an escape from a marble privileged prison (more than an internal, primal drive). These external forces impacting on the lovers thwarted any true reading of classic tragedy – as the fatal flaw within the individual which is their own undoing. As such, the production became less interpersonal and more broadly philosophical about love.

And I guess the lesson is here: Nothing undoes the power of sex like over-thinking it.

]]>