(As an attempt to re-enter, perhaps in a different way from before – I thought I’d start by updating some previous offerings made to the internet. This blog post was written for a show in 2012 exploring homecoming and teenage nostalgia. In my usual cavalier

manner I had pecked it out really quickly and not really thought much about it. I thought I’d aim for a re-entry by going back in time so I might begin to move forward.)

There wasn’t much that was sweet when I was sixteen.

Living in a small coastal town near Woolgoolga in the banana belt of NSW, there was little that linked me to the outside world. TV was limited to 4 channels, I was secretly obsessed with Paul Reiser from Mad About You, I was glued to Helen Razer’s voice and song choice on Triple J like a grommet clings to his surf board at Woopi Beach.

All the while my face was buried in suspiciously pristine ancient history text-books provided by the high school with the vain hope that education would set me free from the shit hole I was trapped in.

It was the 90s.

The dawn of the information age. The Gulf War. The Chechen War. The Bosnian War. Kosovo. Australia was having a recession it had to have. Bill Clinton played the sax and his sperm was found on a dress owned by a woman he did NOT have sexual relations with. Kurt Cobain had moaned his way through gritted teeth and a floppy fringe, then blew a hole in his head.

Sixteen, in Woolgoolga, was not so sweet. For many it signaled a grand leap into an unplanned pregnancy, a sensible apprenticeship, or the school certificate or suspensions for crafting bongs out of orchy bottles in full-view of a lunchtime supervising teacher.

Sixteen was my year of joining a punk band, writing abusive songs, the obligatory occasional social binge drinking, studying Hamlet, unrequited love affairs with boys who listened to Pink Floyd, memorizing slabs of T.S Eliot – all while topping my class and dreaming of my emancipated adult life.

I dreamed of a bright future where I didn’t have to ever, EVER confront the boring, dull, flat unprofitable world I was forced to grow up in.

I dreamed of never having to run (or walk) the cross country, attend a swimming carnival or sports carnival ever again.

I feared that my future grown-up self would have to navigate a school reunion. I hoped I could forever avoid it. And earnestly hoped by the time it rolled around that I had made something of my life. Something. Anything better than the here and now.

At high school, kids wearing an improvised uniform sucked smoke from juice bottles and grinned through red eyes at their future. Flannelette shirts flapped as teens set fire to bins. Grunge was born. I dressed in my grandfather’s clothes and listened patiently as boys my age fumbled around with Metallica riffs on nylon string guitars. River Phoenix died and girls at my school attempted suicide. We were lectured on AIDS ad nauseum and spent long afternoons rolling condoms onto bananas, whilst the cooler kids were practicing the real thing in the bushland that surrounded my school.

It all felt pointless really.

Skinny girls with no opinions got the boys, then had scrag fights on the school bus. Their earrings ripped out of ears. Blood. Torn singlet tops. Swearing. The boys would look on with dull eyes and would not dare intervene. I sat quietly and wrote letters to people I had met who went to ‘other’ schools – a life line to the life outside my hometown.

Inevitably, someone’s cool parents let us have a party at their place. I’d sit planning my future escape and watch as others had fun: Passion pop and Jim Beam. Malibu and Coke. Bongs. Magic mushrooms. Teens gnawing sloppily at each other’s faces, having a casual vomit, a micro-sleep, then continuing. At some stage a posse would form and we’d go on ‘missions’ stealing street signs or garden gnomes from unsuspecting homes. We ventured into the banana fields and sang Nirvana songs to keep each other awake. Lying on the ground on deserted country roads under the stars, we soaked up the warmth from the black bitumen and raged over arguments about reality and perception (teenage philosophy a plenty.) We knew it was all empty, all pointless – the universe too big, the world uncaring. Everything had been thought of before, everything had all been said before. We knew poverty could not and would not be ended by Bono or any other aging rock star who chose to wear rose-coloured sunglasses.

It wasn’t sweet. It was bitter.

Flash forward 16 years.

At the start new millennium the school reunion is unavoidable. It’s not a physical thing – it’s the casual surprise of a Facebook ‘friend’ request… sometimes from someone who has changed their name and judging by their photo has either regressed thirty years or had a baby.

Although I’m a world away from a drunken pash in the banana fields, the sting of school remains: the pointlessness, the feeling of being trapped in a shit hole, the dreams I had, the pressure I felt, the boys I loved, the friends I had. I watch the film clips, sing along to Hole or Pearl Jam.

And suddenly, even mentioning it, here and now, I find the memory is not bitter. Not at all.

The further away one has from the heat of the moment – the awkward daily agonies of being sixteen – the more remarkable those moments are. The moments in which we determine our future, assert our identities, decide on a direction.

It’s sweet.

]]>

Every now and again there is a production which stumbles into the light, into the expectant eyes, minds, hearts of an audience and explodes with such intelligence, rigor and joy that it is irrepressible. The audience squeals and hums with delight, the box office is exhausted and the artists have that warm, nourished glow of knowing that the work will sit as an ultimate touchstone of true delights in their wide reaching careers.

Peter Evans’ production of Justin Fleming’s re-penning of Tartuffe is one such production.

The reviews have been glorious, syrupy effusions – full of praise for the production, the script and performances:

John McCallum The Australian

Polly Simons for Stage Noise

Chris Hook writes for The Daily Telegraph

Jessica Keath for The Guardian

Ben Neutze for Daily Review

There has been in recent years a fairly hefty national discussion about the role of adaptation on the main stages – best read Alison Croggon for the overview, the question of Australia’s theatrical exhaustion as proposed by Dr Julian Meyrick in his platform Paper “The Retreat of Out National Drama” which you can read about here and also what constitutes an “Australian Play” – best read Jane Howard here. – and yet most of these concerns melt into oblivion when there is a production like Tartuffe staring us in the face.

As a long time cheerleader of Australian playwrights, and a long time skeptic of the notion of classics for classic’s sake – Tartuffe answered many industrial injustices I have for a long time squirmed at. My quibbles about the ancient western canon being trotted out by mainstages like a trophy wife of international cultural capital, are fairly basic and point to the sticky and undesirable residue of Australia’s lingering cultural cringe. Such quibbles include:

1. The tendency for classic text to be delivered in a variety of British accents (yes even mainstage productions of classical Greek tragedies have had the royal vocal treatment)

2. The production budget not including a wage for a playwright

3. The complete dismissal of Australian social or political life in reference to the themes and the style of the material

4. A tendency for classical plays to whitewash casting which refuses to accurately reflect the diverse backgrounds of modern Australia on our stages.

5. The programming of classic plays guarantees a cookie-cutter audience development strategies -eg schools – and does not seek to establish new audiences for new writers.

And there are countless arguments about who does this – and how and if we should have cultural KPIs on art -or on audience development. And these discussions will be constant and ongoing.

In the instance of Bell Shakespeare’s production of Justin Fleming’s Tartuffe – we see all these quibbles smashed and reduced to insignificance: the cultural and industrial aspects addressed, cleared the way for what is a production which is uniquely self-aware of nationality, of language and vernacular, of cynical political sensibility – including hearty irreverence and an ability to lean deeply into larrikinism, and of course our exceptional local artists… all aligned under the furrowed gaze of Peter Evans to make what will be remembered as the production to which all aspired to reach the heady heights of what our main stage companies do best.

This is Bell Shakespeare at it’s best – smart, funny, relevant, epic, sexy, saucy, cheeky, brutal fun.

]]>

“Write what you know.”

The first rule of thumb for anyone interested in writing anything. This applies to birthday cards right through to grand epic fictions or a boutique thesis on an obscure historical peccadillo.

It is rapidly followed by the next question:

“What do you know?”

And then swiftly after that,

“How do you know that?”

And then:

“Who are you to write that anyway?”

It is no secret that artists are like bower birds. Collecting snatches of overheard conversation, headlines from newspapers, facts from journals artists chew through the meat and the gristle of daily life, sifting and grinding found concepts, images, speeches – processing it into art. Sometimes the process is curatorial: Selecting and arranging the real, raw data and daily life materials into order or housing them in a shape or place to draw attention to it. Sometimes they work in collaboration with a specific community to reflect a truth or an opinion for the betterment of society – the participants and the audience. Sometimes they fracture reality stylistically, thematically until the work is an abstraction of an idea. Sometimes they imagine an alternate reality, inspired by but not replicating events. Playwrights collect, notate, process and present realities. Sometimes they do all of these things. The making of art is not an easy nor a cut and dried process – everyone does it differently and for different reasons and for different purposes.

It begs the question: are artists parasites of the lives of non-artists?

Recently, as a part of the Independent season at the Griffin Theatre Company, Jane Bodie’s play Music, asks that very question.

“Two actors researching a theatre project befriend a seemingly quiet and ordinary man named Adam. In reality, Adam’s unexceptional existence is carefully calibrated – a precarious sideways tightrope-walk over his mental illness. Now, Adam’s new friends are at risk of throwing his life dangerously off balance. And there’s every chance they’ll go down with him. Music offers a sharp critique of the way mental illness is perceived today and examines the dangerous consequences of raiding people’s personal lives in the name of art. A surprising and surprisingly funny story of people connecting and colliding, as two actors blunder their way into Adam’s life, causing untold damage to him as a result.”

It’s an issue in contemporary theatre writing. An issue we need to discuss.

Artists, despite best of intentions may hurt those they love – friends, family, their community – in the desire to draw on what they know.

As other forms of “reality” entertainment (Reality TV – weight-loss shows, cooking competitions, house renovation shows) push mainstream audience narrative literacy into hardline “realism” – theatre is forced to prove its authenticity, its “realness” amongst the audience. With a glut of homemade, self-made, online content showing “real” events, acts or distractions, content is freely available and accessible. This combination of audience literacy in/desire to engage with reality content and a prevalence of artist access to primary source materials – results in the opportunity for stories outside of an artist’s direct experience to be told.

What does the writer do? Write what they know.

What do they know? They know their perspective based on their research.

How do you know that? They spend time interrogating the ideas, the story, they carry out research and consultations.

Who are they to write this? They are a writer who dares to add to the ongoing conversation about art and humanity which has been in progress across languages, nations, genders, politics, genres since the beginning of time. And to be one small person contributing to that – in the face of peers who will evaluate your contribution – you have to have an iron constitution and know your stuff pretty well.

So it is hardly surprising when a few weeks after opening, there is controversy surrounding The Griffin Theatre’s current production “Ugly Mugs” by Peta Brady (a co-production with the Malthouse Theatre) about the ethics of the storytelling.

According to a member of the Scarlet Alliance, Australia’s peak sex worker organisation, Ugly Mugs is “Pity porn.”

Read reportage from the Sydney Morning Herald here: http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/theatre/sex-worker-union-member-attacks-peta-brady-play-ugly-mugs-20140813-103mty.html#ixzz3AHNyUYFm

A string of alternating responses – praising and damning the production on the Griffin Theatre Company Facebook feed http://www.griffintheatre.com.au/whats-on/ugly-mugs/

It has created a community upheaval amongst sex workers who have articulated their perspective ending with the powerful phrase:

“Sex workers speak for ourselves, our personal stories belong to us and it is our right if, and when to tell them.”

The Griffin Theatre Company responded with a formal response nobly engaging with the issues raised, and open to revealing the consultative process and seeking to continue engagement with the Scarlet Alliance. The objective and the intent of the play was articulated “to provoke conversations in our audience about the steps we need to take as a society to unmake traditions or patterns of violent behaviour.”

http://www.griffintheatre.com.au/blog/response-to-ugly-mugs-blog/

I am not specifically interested in engaging with the particulars of due diligence or artistic license in this particular instance. I think the dialogue we have with audience is as important as the conversation we have amongst ourselves.

The broad issue I am interested in here is:

Who has the right to tell a story?

How do we have a conversation about ownership?

How do we work through conflicts of representation?

Raised at the Australian Theatre Forum in 2013, this issue was raised in the idea of representation and appropriation of Aboriginal story – who has the right to tell a story? Can races be cross cast?

Raised again at Playwriting Australia’s National Play Festival 2014 during an industry session focused on Aboriginal Dramaturgy – what is the process of permission/rights to sharing story, sharing language?

When working in a context which is based in and of a community there are sensitivities to what and how information is shared, where permission comes from, how it is granted to whom and when.

For artists, whose source material is their experience of the world – the structures around notions of community engagement and ethnography are blurred, or casual or not existent.

It can leave artists open to attack. It can leave communities open to attack.

Which is not the objective of cultural and artistic pursuits. Not at all.

Artistic and cultural pursuits seek to bring understand, compassion, awareness, inspire activism and social change. It is this intention which elevates art above the idea of base schadenfreude or entertainment.

And we’ve got to talk about this. This is too important not to engage with.

Telling stories can come at a price: the trust and respect of our loved ones and or our community.

As artists and producers we have a moral obligation to our community – both those who are sources of inspiration and those who are our audiences (hopefully these are one and the same) to make sure that the context in which we develop and make a work involves consultation and discussion with community – and that takes time.

It takes generosity, patience. From everyone.

It will take a willingness to speak. A willingness to listen.

I believe our arts community has the capacity to deliver.

]]>

Children’s content is possibly the most important content in the world – films, music, theatre can create a moral, personal, ethical compass for a child beyond their familial and educational realm. The experience can set up a child for life – or cure it of ever wanting to spend time in or near a theatre. It is particularly difficult as society emerges with children and babies being more photographed and publicly “shared” via facebook and other mediums – than ever before in history. The idea of self, entertainment and non-screen based activity for children has changed and will change from the former frames of work. Children have – more than ever – on-demand access to a wide variety of entertainment and so theatre for children is a competitive sport requiring great nibbleness and a suite of skills.

In theatre, the audience is 50% of the equation – and if the audience is not right for the show – or the show not right for the audience – it can be an unfortunate mismatch. In the realm of children – this is even more of a sensitive topic – whereby certain ages will exclaim that something is baby-ish whilst others will be so bored/disengaged they will wiggle in their seats, look at anything but the stage and ask loud questions of their parents about what is for lunch or why are they there. (All questions definitely worth asking). Sometimes well-meaning parents – citing their four year old is a genius will take them along to a 7-year-olds + performance, only to be surprised that the content doesn’t match the child. It happens.

What I think is more interesting to consider is how the content – the story, the language, the imagery, the stage craft – tells the story it is telling to the audience it is telling it to. And that is the essence of understanding reviews.

But enough with this melange of social theory, philosophy and pro-review propaganda… the matter at hand is The Composer is Dead an orchestral mystery by Lemony Snicket. I couldn’t help but race through Walter Benjamin’s Death of the Author whilst watching this new production. I couldn’t help but think of the notion that this might be an introduction to the Opera House for many young people. It might be the first time seeing an orchestra. I thought of the awe and wonder I had beholding that building for the first time. As I watched I tried to imagine and connect to being tiny and new to art – what would I think of this man in the moustache and all those wooden, twirly, shiny curly instruments?

Then I sat back and relaxed…

Written for www.australianstage.com

Large white sails interrupting a beautiful blue Sydney sky, the be-pebbled concrete of the foyer, the grandeur of a tiered wooden concert hall – offering the promise of something grand, befitting the scale of awe and wonder of architecture.

There is a charm in children’s literature which offers an irreverent playfulness – an element of infinite possibility, and an exemplary example is that of Lemony Snicket. It’s hardly surprising his is a pseudonym – or that he has a revolving biography that offers a fresh take on identity. Everything from: “Lemony Snicket was born in a small town where the inhabitants were suspicious and prone to riot. He now lives in the city. During his spare time he gathers evidence and is considered something of an expert by leading authorities” to “Lemony Snicket was born before you were and is likely to die before you as well. A studied expert in rhetorical analysis, Mr. Snicket has spent the last several eras researching the travails of the Baudelaire orphans” and “Lemony Snicket published his first book in 1999 and has not had a good night’s sleep since. Once the recipient of several distinguished awards, he is now an escapee of several indistinguishable prisons. Early in his life, Mr. Snicket learned to reupholster furniture, a skill that turned out to be far more important than anyone imagined.”

It’s a mystery!

As is the latest local production of a show commissioned by the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra “The Composer is Dead!” Written by Nathaniel Stookey with text by Lemony Snicket, it is billed as a “cutting-edge introduction to the classical music.” What it is though, is an introduction to an orchestra, to the humour and philosophical musings of the very, very clever Lemony Snicket. On this occasion the joy and delight of orchestral music is placed firmly in the baton of Brian Buggy and the Sydney Youth Orchestra – and the joy of interrogation and vaudevillian ham in the agile wit and charm of our host Frank Woodley (comedian /professional show off of “Lano and Woodley” fame who has also starred in Thank God You’re Here, Bewilderbeest, Optimism, Inside)and directed by Craig Ilott (Hedwig and the Angry Inch, Smoke & Mirrors, La Clique Royale). It is less an introduction to classical music and more a witty expose of orchestral identity riffing on classical music from the Western canon.

It is nearly impossible not to want our host to succeed – he’s self-reflective, goofy, awkward and determined – and we love him for his terrible moustache and because he is easily flattered by the woodwind section. In the spirit of Snicket, Woodley is playful, energetic and clever – and it is a big stage, a big orchestra –he swings through the sections always keeping his eye on the prize – us. It’s a big ask for such a big room, and Woodley and Illot serve the story and the context with grand gestures befitting of the backdrop made of swathes of red velvet.

There is a simplicity in the production that is appealing – charming in the grandeur of it all. But there is a disconnect between the concept of an “introduction” and a playful riffing on assumed knowledge. Unfortunately the former is not sufficient to support the later – and the show itself is best pitched to those who have some prior experience of orchestral music who are ready for the references and the knowing nods to composers (and decomposers) to slide slickly into the story.

For any child and parent familiar with the grandeur of classical orchestral music The Composer is Dead is guaranteed to amuse and delight by the mere charm of simple story told well.

]]>

Dragging my feet like a reluctant school child. I’ve been on the verge of writing so many times and yet prioritized everything above this task. It’s a fear of mine – deep and dark and quiet, cruel and steady, so casual in it’s proliferation – apathy.

I dread apathy. I fear complacency. I feel compelled to guard against it. I sometimes feel the righteous burn of wanting to rid it from those around me who weakly concede “but that’s how the system works,” or “that’s just how it is.” We lack imagination and ambition with that line of thinking and I can’t help but feel the deep need to build on the legacy of what has got us this far: the vision, bravery and fortitude to do something new, something better.

Occasionally I come across a play which is so urgently shouting it’s lineage and credentials, that I am forced to step back. Rocked back in my heels at the sheer weighty tidal wave of effusive significance or pedigree or accolades.

Such things always gives me cause to pause.

Mojo by Jez Butterworth is one such occasion.

Mathematically this production should add up. Talented director, talented designers, talented cast, hot zeitgeist aesthetic. But really there was something lacking.

Sitting there waiting to be transported or transformed I felt myself detaching from the world in front of me. Sitting aloof and indifferent – at best thinking “clearly there was no need for women in the 1950s in England” at worse thinking “why am I watching this? What is this saying to me?”

In 1995 when Mojo first stumbled across a stage in its first trembling steps, the neo nihilism of grunge was sweeping the world. The utopia of the previous generations offering love and peace was an empty promise and the resulting cynicism left those in its wake seeking numbness. Since then, candy-coloured pop music film clips have sought to compensate – offering Katy Perry and cheesy glamour as the antedote to contemporary western culture’s symptomatic depression. But in the 90s, the 50s cool was still keeping on – the legacy of James Dean, Happy Days, Grease – easy and familiar silhouettes on youthful memory. Cool was everything. Still is. So not surprising the clash of the above ground and the underground was such fertile soil for so many. I think about the context – beyond the particular playwright – into the large narrative of time and culture what this contribution means.

Perhaps what has happened in my reading of this play – in my context here and now – I’ve seen, read too much and so the naive unselfconscious ramblings of the boys in Mojo appear to be derivative (even if it did precede the flood gates of homage, retro 50s fascination). Referring to Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels, Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction… or any Jacobean tragedy or series of Channel 9’s Underbelly.

What I found most difficult about this play is how little I cared for or about the characters, their fate, their past – the story.

When I don’t care, I find it hard to share. When it’s hard to share, I don’t want to write about it.

And that inaction nearly destroys me. And so I write. Write something. Anything. Just to prove that I’ve not been beaten by apathy or complacency.

Written for www.australianstage.com.au

It’s dripping with Retro chic in every way possible. Sydney Theatre Company’s latest Wharf 1 offering has rockabilly, hipster fanfare written all over it: the promise of a 1950s rock and roll, dark gritty underbelly time capsule. An edgy feast for those hooked on the heavy thud of booted bovver boys, or so the Artistic Director’s note and the Director’s note suggest.

However Jez Butterworth’s Mojo is not delicately laced with the quaint tinge of nostalgia that retro acts of art can bring a contemporary audience, but drenched in design and nearly pulled under in the near two decades of gang/drug/thriller genre-content offered since its premiere in 1995.

The premise hangs on the fate of a single character “Silver Johnny” and the den of corruption and desperation that seeks to control his unstoppable talent. In the wake of real-life pop-star scandal (Justin Beiber, One Direction, Elvis Presley) and the subsequent spread of film, TV and gaming media geared to the underbelly or ganglands of other places/other times. This is a fairly familiar tale, told by Butterworth in a fairly unsurprising manner.

Though dutifully and deftly delivered by a very capable cast – Jeremy Davidson, Eamon Farren, Josh McConville, Lindsay Farris, Ben O’Toole, Tony Martin – and underscored by the musical ruptures of Alon Ilsar and Paul Kilpinen – Mojo falls short of the explosive and effusive praise quoted in the program.

Iain Sinclair with an all-star team of Pip Runciman (Set Design), David Fleischer (costume design), Nicholas Rayment (Lighting design) and Steve Francis (Sound Design) has produced a handsome and technically coherent piece of stage work. But the play’s the thing. And it failed to inspire or intrigue.

Running at two hours and thirty minutes, including interval, it runs for about as long as Quentin Tarrantino’s Pulp Fiction’s theatrical release (which was released a year earlier in 1994) without much of the glamour, humour, quirk, craft or curiousness. The story unwinds in a simple and unambiguous, linear fashion collecting moments of individual revelation from each character. The affect is an inordinate amount of steaming, stamping, brotherly drug taking, sexually ambiguous threats, some stale cake, some powerful guitar and a couple of bloodied garbage bins.

To what end? Is this a portrait of another time – to be regarded with the reverence of ages past? Is this an attempt to show the downfall of drug taking? Or the downfall of joining a gang or a band? Is this proof that men are essentially self destructive? Is this story to show the latent power of the next generation? And what do we learn?

It appears that the retro chic design of this production, fails to elevate the play above the resulting onslaught of like-genre parables of boys behaving badly.

]]>

I’m not a journalist. I’m not an academic. I’m not a lawyer.

I’m an artist.

I’m an artist who has sat in a very weird place in the Australian theatre landscape somewhere between producer and critic, emerging and established, between fan and assessor, audient and philanthropist, administrator and promoter. It’s not due to a lack of rigor – or ability to commit to one thing. My attention is not diluted nor compromised because of my sprawling embrace of all things art and culture. In fact, it’s intensified. There is little else I could imagine that could exercise my heart, my mind so intensely and so perfectly.

There has been, since 2012 a drop in my ability or willingness to flex my public muscle as what some see as a “critic.” Namely a series of very distinct, personal attacks, a death threat and general occasional social isolation which sometimes has been warranted. However, my passionate engagement has not stopped though it has steadied. I feel less inclined to dig into the finer silt of an argument regarding art… because in my experience it too often dissolves into an ugly personal attack of “who do you think you are anyway?” That line of attack, I felt inclined to respond to with equal vim and vigor stating my claims and justifying my right to an opinion, a voice, a position.

But now I no longer feel inclined to get muddy in this silt.

I’d avidly read and unpick Alison Croggon’s Theatre notes comments with eager attention:

http://theatrenotes.blogspot.com.au/

I’d watch the well handled disputes on Jane Howard’s blog:

http://noplain.wordpress.com/

I’d watch as the Sydney theatre critics became a safe and watery horizon of obvious mainstream platitudes and see the rise in popularity of what I personally refer to the “marketing blogs” containing sweet sentences of praise for any production providing a free ticket – without any hint of an argument or perspective with grunt or muscle. It’s easy to be in the soft safe nest of fawning reportage – much harder to try and move the conversation into broader perspective. Much harder to exclaim the nakedness of the emperor. Much more painful when your truth has you burnt at the stake.

The thing is we all get it wrong.

Artists. Critics. Producers. Audiences. Funding bodies.

Everyone.

Everyone gets something wrong sometimes.

Sometimes we speak too soon. Sometimes we don’t speak soon enough. Sometimes we use the wrong words. Express an idea the wrong way. Sometimes we misjudge, misunderstand, miscommunicate. Sometimes we use the wrong forum or medium. No one gets it right all the time.

What matters most is not how often we get it wrong or get it right – after all art is largely about pushing boundaries – it’s about how we recover, how we resolve differences, how we admit when we’ve gotten it wrong. How we stand up when we know we are right.

Last week Australianplays.org posted an essay by Jana Perković http://australianplays.org/the-australian-bad-play

“Apocalypse stories in which the plot centres around romantic triangles and suburban drug-taking. Four-handers in which none of the characters talk to each other. ‘Issue’ plays in which current political events are lightly fictionalised, their very existence meant to be the heart of the drama. Or: recent creative-writing graduate departs for a year of backpacking and reality; the drama hovers gently between ‘loss of Australian innocence’ and reportage, not quite hitting either note. Working-class people die of abortion, drug use, broken-homeness and living in outer suburbs. Arts worker returns home and spends the entire play in subtext-laden silence at the family table. Four people sit in the evocative Australian landscape and talk about art. Four people in the big city talk about politics. Three or four teenagers talk like teenagers do: no plot.

I’d like to introduce you to Australian bad plays. All of them, however disparate they may seem, have failed in the same way – the Australian way. Plays of this kind appear on dozens of Australian stages every week between Wednesday evening and Sunday afternoon. And at the end of each one, the audience comes out of the theatre saying to each other, politely, but without conviction: “Well, that was interesting, wasn’t it?” And the choice of timid non-commitment instead of passionate rage expressed here, outside of our half-dozen hypothetical theatres, is only another instance of the rhetorical substitution of niceness for truth that had happened inside. The failure of the Australian play is the same as the failure of the Australian dinner conversation, television discussions, and public debates. Not all Australian plays, dinner conversations, and public debates fail in their purpose; but when they do, they fail similarly.”

The most interesting aspect of this essay is the idea of “Australian failure.”

Perkovic is asking a broader question of culture – suggesting a nation propensity for conflict avoidance, or an acceptance of the repressed and a denial of confrontation. Is this true? Could it be true? Is there a cautiousness in Australian playwriting – or is the cautiousness in Australian play production which leads to a series of new works to demonstrate a stylistic or thematic disconnect with conflict, action, confrontation?

Unfortunately the conversation has been derailed by several factors – the ethics of siting an unpublished, unproduced work Perkovic obtained in her role as literary manager is one, another the robust and relentless tone and scale of the essay: it feels personal, not academic.

Since the 29th of May when the essay was launched, it has been edited, sections omitted, has stirred 30 or so comments on the australianplays.org site and countless other threads on personal groups and Facebook pages.

This afternoon Tom Healey issued an apology and response: http://australianplays.org/an-apology-and-a-response

I’m left wondering – will this apology and response be enough? Has there been so much damage done? What is the damage? Reputational? Industrial? Can we ever have a difficult conversation about art if:

1. We always play the man and not the ball?

2. We never allow anyone – artists or critics – to make a mistake?

3. We can’t in a civil and respectful way engage with mistakes and try to lead by example?

What I am coming to the realisation is this: perhaps we as a culture are not ready to have a critical conversation?

Perhaps we are too fragile, too angry about the state of our respective fields (critics often underpaid, under resourced, disrespected and artists often underpaid, under resourced, disrespected) to actually address the issue of art, of culture for the benefit of current and future thinkers and makers.

Perhaps there should be no discussion.

What then?

Would we all be happier?

]]>

As a teenage girl, Kafka’s A Hunger Artist was a story I read and re-read. This would only seem strange, I suppose, if it was true that Teenagers are NOT the most philosophical (and existentially angsty) humans on earth… and if I didn’t grow up in a small town which I despised for being small and a town. Reading was a consolation. Reading Kafka even more so. I could have spent a lot more of my time flirting with and then dodging teenage pregnancy, but instead I was reading A Hunger Artist, and thinking about the tragic cruel truth behind Kafka’s portrait of the fickle, skeptical general public. If you wasted your childhood in more interesting/sexy ways, perhaps you’d like to read the story here: https://records.viu.ca/~Johnstoi/kafka/hungerartist.htm

(Though NOT reading it will in no way prevent your curiosity in Clockfire Theatre Company’s latest offering: A Hunger Suite)

The story is summarized thus:

“The protagonist, a hunger artist who experiences the decline in appreciation of his craft, is an archetypical creation of Kafka: an individual marginalized and victimized by society at large.”

Taking this story as a departure point, Clockfire Theatre Company has investigated and re-presented the notion of the rejected artist in a surprising way – a series of scenes, images and chapters brimming with effort, with desperation, with humour and charm which captures attention and wears out its welcome into an absurd spiral of fatigue and pathos: a desperate hunt for validation, for attention or recognition.

Presented in the Old 505 Theatre – in my opinion, the venue in Sydney currently boasting the most exciting, innovative, interesting and challenging independent program – I was lucky enough to witness the first draft of this work in 2012, a bizarre and surprising patchwork. This was a draft before director Russell Cheek offered his eye, intellect and aesthetic to the project… before a composer and musician Ben Pierpoint gave breath to a bouncing bassoon… before a residency in Istanbul solidified and clarified the story, the feeling, the overarching look and feel of the production.

The result is not so much a linear story – after all this work is about performance, not about literature – it is about sensation. Using the audience as implied antagonists, the story reaches into the audience to fatigue us, to ask us to be fascinated, then bored, then disengaged. The effort which is squeezed out of the performers takes us on a parallel journey into the narrative. Performed & created by Emily Ayoub & Mine Cerci, through out the course of the evening we are directly spoken to, profusely thanked, tap danced at, asked to accept the transformation of person into horse, into limbless Cartesian horror. It’s strange, strange making and surprising. Echoing afterwards is the residual poignancy of the performer… discarded by the public. Forgotten. Useless. Rubbish.

This is difficult, beautiful performance. Abstract, beguiling and hilarious.

And if you see it, you’ll know I am right.

If you don’t go see it, it means Kafka was right.

Either way, I’m satisfied.

A Hunger Suite

Presented by Clockfire Theatre Company

http://www.clockfiretheatre.com/#!a-hunger-suite/cc5y

Performed & created by Emily Ayoub & Mine Cerci

Directed by Russell Cheek

Music by Ben Pierpoint

Old 505 Theatre, 505/342 Elizabeth St, Surry Hills

7-25th May 2014

Times: 8pm Wed-Sat, 7pm Sun

Doors: open 1/2 hour prior to performance start time

Tickets: $28/$18

The risks are great – not counting the obvious financial risk which touches all artists – new work takes a bit of hustling. It takes convincing of actors (and their agents), venues, audiences to invest time, energy and attention in something untested, unknown. When I am watching a new play – particularly in the independent sector – I consider that the actors must believe in the fundamental message, style of the play. I see the actor as an important participant in the curation and development of culture, ideas and I hold them accountable for their choice to be involved. The actor’s contribution is huge – and signals to me their values as a person and an artist in their support of the writer and director. The act of anyone committing their time and attention to a new work is an act of faith – an act of hope some might say – in the possible.

However, it can happen that what is generated can not and does not reach beyond the aspiration of moving the artform forward, or touching an audience. There’s the possibility that the production falls short, confuses, bores, baffles, exhausts, disengages.

The Australian contemporary playwright has a lot to contend with:

The history of theatre

An international pallet of performance styles

A huge back catalogue of great plays

Film

Literature

Interesting dinner conversation

International contemporary playwrights

Fads, developments and fashion in playwriting as a contemporary practice

YouTube

The Internet

Facebook and other social media

A literate, mobile, educated audience

Limited production resource

Differing performance styles, interests and experience of your cast

The physical limitations of the performance venue you are working in

As such the content, form, style has to be coherent, well thought out, well considered, timely, innovative, fascinating.

If the play is written in a series of re-enactments – without exposing the current issue, the audience is disconnected from the present, the work is not urgent and so meanders. If the characters are written to caricature or type, the audience has little to discover beyond cliche. If the mechanics of the play, for example stage management or set changes are brought into the play – it must serve the story, the theme or the message – otherwise it will appear gratuitous. If the characters tell the audience their inner psychology or expose their motivation which is in clear alignment with their action: the audience has no reason to lean into the play and discover anything for themselves. If the audience becomes aware of a change in lighting state, it is often to indicate a change in scene, mood or idea – if the lighting state does this without a thematic or structural change – or even to express a time of day, it disturbs the audience, without any pay off. If the character is established as angry and didactic at the top of each scene, there is little opportunity for the character to develop. If there is a character that is constantly making jokes or commenting on another character’s vulnerable reveal, or on an important monologue which is there to serve to cohesively bring all aspects of the story together: the audience can become distracted by the commentary, and not pay attention, nor give much weight to the message. The premise is everything. The characters status is important – shifts in status must serve the story, the message. Likewise a change in furniture must serve the story, or the space: remove a chair and you change the world. Is it true that a police officer or sargeant has infinite time to hear the self-aware, self-reflective memories of a criminal? Grant a prisoner freedom to walk out and get a cup of tea, and the premise of the scene is no longer respected as holding any gravitas. Tell the audience what the play is trying to say, eg “There is always hope” and they’re less likely to believe it, than if they were to walk away thinking and feeling there is always hope.

Additionally the question needs to be asked: if your question or premise of your play is, for example “is evil created or is evil innate?” – it might be worth considering if that is what your play is about. If perhaps your play is not about that, but about hope, it how important it is for the audience to know the conclusion of such a discussion “There is always hope” before they’ve seen the play?

Amanda is a play which requires some rigorous re-drafting, reconceptualizing if it is to overwhelm and bypass stories (plays and films and novels) which touch on similar themes in the cannon eg: No Exit, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, Wolf Lullaby, Hedda Gabler.

Amanda

written and directed by Mark Langham

performed by Amylea Griffin, Paul Armstrong, Elizabeth Macgregor

“”What did you do?” Was Amanda born this way or has circumstance made her what she is? What is she and, where is she? A new play from this multi award winning writer tells of our disconnection from each other, the ease with which we distance ourselves from others and much more. It does it with this writer’s customary wit and directness and is so sharp it may cut.”

May 13~18, 2014

Downstairs Theatre, TAP Gallery

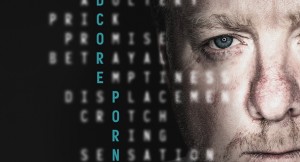

Shag pile, shag pile everywhere – even climbing up the walls.

And just as well, too. I need somewhere soft to lean into, while sitting in the dark breathing in the words of Declan Greene’s Max Afford Playwright’s Award winning play premiering at Griffin Theatre Company – the provocatively titled “Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography.”

The Internet.

The latest in a string of many human lead historic revolutions – following the mechanical and the sexual – to improve and yet collapse the world as we knew it in the same moment. A place where Avenue Q exclaimed (and we’ve been chanting ever since) “The Internet is for Porn.”

It has be come the most powerful double edged sword for priviledged societies – presenting both democratization of information and prevalence of bullying, access and anonymity for individuals to provide, explore or share all corners of one’s thinking, personality, opinion, persona. The internet has made us clever quick at finding answers and yet lazy in our research and recall. The internet has provided a place for people to lance their emotional boils in chat rooms, in comments on social media sites. It has created a mighty swirling archive of grand human endeavour, curiosity and pettiness. The Internet has opened up a flood of thinking – good, bad and ugly- from across the globe (except maybe China) and has encouraged people to actively participate in its creation, maintenance and curation. It has made readily available some of the most astonishing moments of human interaction, linguistic disintegration/creation and crowd thinking…

The Internet is a huge, wild, restless Leviathan which saves and destroys with each key stroke.

The Internet is, really, in essence, the harnessing of human kind in all shades of emotion, thought and action.

That is what makes it so terrifying.

What makes it so terrifying is that we make the content and the content is shaping us… No doubt you’ve seen Gary Turk’s call to “Look Up”?

Declan Greene’s play is a portrait of the resulting effects of the internet: where there is access open to compulsive spending and obsessive lust…

The blurb goes like this:

“They met online. She’s a nurse in her forties, brats for kids, trapped in a loop of catastrophic debt. He’s in IT, miserably married and trapped in his own loop of nightly porn-trawling. Both of them crave something else – but not necessarily each other.

Take the plunge into the Too-Much-Information Age. Funny and fiercely written, Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography is a deceptively compassionate cringe-comedy of mid-life loneliness, hidden zip folders and barely concealed desperation.”

Declan Greene’s Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography is a brutal spectacle exposing extreme human gluttony as a defense mechanism against disconnection, loneliness and frailty.

Here he exposes all too familiar shame and guilt and impotence of modern life – the secrets we keep that gnaw and erode.

Life full of compulsive spluttering lust and urgent frivolous material acquisition.

And it left me reeling in a car crash hypnosis…

In an interview conducted by Elissa Blake the headline states “Playwright Declan Greene says Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography isn’t repulsive.”

And I would agree by adding…”Eight Gigabytes of Hardcore Pornography isn’t repulsive any more than the uttering of a painful truth or the revelation of shame or trembling lost vulnerability is.”

Ideas expressed through the flesh of two actors, Steve Rodgers and Andrea Gibbs, the direct address places the audience as possible love interest, best friend, counsellor or confidant – they switch between story teller and enactment as swiftly as the mood shifts and changes. The writing is fragmented – sliced up into fourteen scenes.

The designers – Marg Horwell (responsible for Shag pile and costume), Matthew Marshall (light) and Rachael Dease (Composer) – work within Lee Lewis’ muscular direction – keeping bright and ready a darker moment in the story and sugarcoating reality.

However, some aspects of the direct address push me away, asking me to observe a reflection or rumination or realisation – instead of asking me to connect directly to action unfolding and by that I mean inviting me to “lean in.” The affect is ultimately one of an intellectual exercise of understanding and weighing what I’m told with what I assume or already know. The moments which swept me up and away were predominantly watching Rogers react to Gibbs contrasting to the dialogue spoken because I felt I was working harder to find the truth- not being told it plainly.

There is a value in taboo, in speaking the unspeakable – and though these topics and revelations have been covered in literature, in newsprint and in online forums – hardly are these confessions spoken publicly. What must be congratulated is the work of both Declan Greene and Lee Lewis to expose and present this contemporary crisis we are experiencing where we sabotage and self-harm through secrecy or through gluttonous excess. We are ultimately the ones who will bring about our own downfall – and that message has often been told. What is interesting is the possibility that we might also be the answer to our own salvation as we catch our reflection in the blade of a double-edged sword.

BOOK

Phone 02 9361 3817

Online http://www.griffintheatre.com.au/whats-on/eight-gigabytes-of-hardcore-pornography/

PERFORMANCE DATES

Previews 2, 3, 5, 6 May

Season 9 May – 14 June

Subscriber Q&A after the performance on 20 May

PERFORMANCE TIMES

Monday – Friday 7pm

Saturday 2pm and 7pm

RUNNING TIME

Approximately 90 minutes with no interval

VENUE

SBW Stables Theatre

10 Nimrod Street

Kings Cross NSW 2011

That familiar twist and turn of the road, pitted with holes and crumbling bitumen – I’d look up more at the arcing trees if the twists and turns and the potholes in the road didn’t keep my eyes wide, and darting about – Callan Park.

Callan Park. Previously a meeting site for the Eora Nation, looking over the harbour, now houses so many people, so much potential so many pursuits. Usually I find myself lost on this greenspace’n’ gravel headed to The NSW Writers Centre, or wandering into sandstone buildings with red wine and stained shoes looking at graduate art from Sydney College of the Arts, previously I had been helping a Canadian punk band find their way to The Laneway Festival. On this occasion, for Inner Garden, I was anticipating the new work by Bodyweather practitioner, aesthetic adventurer and performance maker Tess De Quincey.

Having a fifteen year relationship with an artist’s work really matters. For me at the opening of De Quincey Company’s Inner Garden, I felt like a rush of embodied experience finally settled and made sense – like the tetris game was now under control and I wasn’t just experiencing a stacking up or overloading. I’m not sure if it was this particular work, or if it was me – but I felt for the first time, completely spellbound. Previous experiences of De Quincey’s work I felt removed from the ideas – outside or inconsequential to the happenings around me. Inner Garden a completely new mode of engagement – welcoming adventure, an aesthetic treasure hunt of sorts – in a space which I had previously had cursory experiences in.

Elemental and elevated, a man wrapped in plastic sprays gentle spikes of water from the rooftop of the courtyard. Inside the front door a woman is hung up-side-down, carefully watched by a rigging assistant, a gardenbed smokes with a resting body within, other bodies – feathered or armored in leaves hide and shift. There is: cluttered furniture with deliberate graffiti, paper aeroplanes shuffling along a string whilst the evening Sydney sky is interrupted by the heavy exhalation of a aeroplane, a table full of curios and variations on clay and ink and sand themes, a web of cord holding up a boulder, a corset lit by a shard of light dusted with sand, a self perpetuated drum machnine made of bits of tin and drum and wire hidden under a franjipani tree.

Hidden adventures.

The hidden.

Interestingly the connection to land and place and history is probably what made so much sense to me. Callan Park is a beautiful place which sits above a series of tunnels. Earlier in its history as a sanitorium it was considered that the inmates were not to step on the queens land, and so travelled underground. An interesting architectural history too – The lunatic asylum was designed according to the ‘enlightened’ views of Dr Thomas Kirkbride – the idea that architecture (like all art) can help soothe and restore the mind has a long history. Interesting for me the feeling of being locked into a cloister was not as oppressive as I had assumed – perhaps due to the large stretch of night sky- which switched it’s colours from light blue of the day , through various shades of magenta into a dark blue night.

The shift in the work from solo struggles, acts of defiance, aggression, physical/vocal/emotional exertion – to group vignettes – a push or pull, a chasing interweaving – punctuated with timekeeping by a gong. The regimented obedience, the discipline within the chaos.

Beautiful, difficult, spellbinding Inner Garden is to date one of the most sophisticated, intricate and daring installation performances by De Quincey Company.

Dates: 6 – 8 February 2014

Location: Callan Park

Tickets :Full $35 / Concession $30 (plus $2 booking fee)

Concept & Direction: Tess de Quincey

Performers: Victoria Hunt, Linda Luke, Ellen Rijs, Kirsten Packham, Lian Loke & Garth Knight, Weizen Ho, Latai Taumoepeau, Yoka Jones and Dale Thorburn

Installation & Costumes: Tom Rivard & Katja Handt

Sound: Jim Denley, Kraig Grady and Robbie Avenaim

Lighting: Sian James-Holland

Bookings: https://innergarden.eventbrite.com.au

(A short note to apologize for the lateness of this post – a tumultous couple of months full of distraction and duty has lead me a way from celebrating this work – and my memory seems too soft to offer any grand sharp incisions into De Quincey’s practice – but I wanted to note an record this, regardless)

]]>