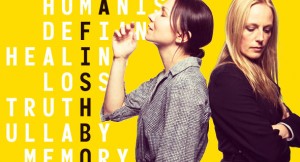

Like A Fishbone | Griffin Theatre Company & Sydney Theatre Company

- July 26th, 2010

- Posted in Reviews & Responses

- Write comment

It’s not easy taking a punt on a new play, and the scariest punt imaginable is the play which is absolutely positively new and from an absolutely positively new writer. In this case the sleight of hand is interesting: and the context is interesting. The Griffin Theatre Company and Sydney Theatre Company have joined forces to produce Anthony Weigh’s new play “Like a Fishbone.”

Some may have seen Lee Lewis’ production of Weigh’s 2000 Feet Away, which was programmed as a part of the B Sharp Season in 2007 (which won the Sydney Theatre Award for Best Independent Theatre Award in 2007), but since that time Weigh has had plays produced at The Bush Theatre in London… including Like a Fishbone in May/June 2010.

The punt in this circumstance is programming a play by an Internationally based Australian playwright, whose world premiere happens months before the Australian production- and watching the reactions to the script in Europe before it heads to Australia. It’s an interesting case. When a script is produced in one place, in the hands of one director- is that then to be the definitive script? Is the published book in my hand the copy that was also used in the Bush Theatre production? If it is received well there, will it be received well here? And vice versa?

I rarely read anything about the plays I review before I see them. Often I am drawn to a particular artist- writer, director or performer… and I have certain theatres/venues I like to attend- and I happily declare my hand. I choose to go where the Australian writing is. I choose to look at the new plays… I find it an amazing challenge and a thrilling agonizing pressure/pleasure to be the receiver of the newest of the new. So it is no surprise that I have favoured the stages of the Griffin and Belvoir and The Old Fitz- the three at the forefront of new work.

I make it a policy not to know too much before seeing the play… which can make it difficult when wooing a date to come along with me. Often I will be asked “what’s it about?” or “is it going to be good” and the glib response of “I don’t know” pops up in response to both questions… and so I send a link to the potential date… and await to see if there is something appealing in it for them- always an interesting litmus test of the market appeal of a play… and depending on how the show goes says something about the bravery of my date… or in the compelling nature of my company.

Sometimes, I have the great fortune of having the mighty mind of Mr Waites to bounce off- we have turned to each other and said “WOW” simultaneously… we have delighted and been dismayed by many shows together… but regardless of his opinion, I always remain true to my gut response when I write. And so…

I write my response. (So swiftly, it seems that grammar and spelling are sacrificed in the finger-pecking fury.)

I finish.

I post.

Then I read what everyone else has to say. In this circumstance I then read:

http://eightnightsaweek.blogspot.com/2010/07/review-like-fishbone.html

and I saw that Elissa Blake had given the play a 9 out of 10… and then I looked a little further afield and it appears that the critics in the UK had quite a different response to the text:

http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/theatre/review-23845046-like-a-fishbone-sticks-in-the-throat.do

http://www.ft.com/cms/s/2/b89088b8-7ad8-11df-8549-00144feabdc0.html

I draw attention to this not because I think there is a right and a wrong way to read a play- either in text or in performance- but to show the different discussions. I have reservations about this piece as anything more than an interesting intellectual wrestle. I also feel that the play may have started in the wrong place… where the conflict begins- is this an internal conflict or a theoretical one- is it international or completely domestic? What does it mean to be transformed? (Yeats ringing in my ears: “transformed utterly… a terrible beauty is born”) What are we left with, once all the words and thoughts have been spoken. We have wrestled verbally, intellectually and physically- and we are left with…. what? A broken song from a remorseful mother?

No doubt about it- a handsome production- and Griffin and STC must be proud… It is a punt I am thrilled to see happening. An Australian play with an international profile- nice.

Also quite thrilling was Cate Blanchette’s acknowledgement of the traditional caretakers of the land on opening night. Five stars for that acknowledgement up front! But I must slightly suggest that Griffin should not be referred to in the diminutive as a “small theatre” partnering with a “large theatre”… As far as I am concerned, the Griffin is one of the most culturally significant institutions of Australian Theatre- it is the home of National Playwriting… Out of that space (previously known as The Nimrod) Belvoir was born. Let’s not forget, that though small in stature, The Griffin punches WELL above it’s weight. And always has.

This review was originally published on https://www.australianstage.com.au/

White drops of rain trickle in luminescent light down the wall of an office. On a table in the room is a white model of a town. There is the sound of the rain in the streets outside.

In an architect’s office a blind mother waits. She has travelled by bus to talk to the architect. She has travelled by bus because of trackworks. Trackworks because of the flooding. It is raining. She is wet. She waits. Confronted by a voice of a woman, the mother asks to see the architect. It is soon explained. The woman is the architect. “You can be both.”

The architect is responsible for designing a memorial after a community was devastated by a tragic shooting at their local school. The mother feels responsible for passing on the wishes from her daughter: that the memorial is not what they want.

Both women equal in many ways: fierce, intelligent, passionate and yet completely different in world view… completely opposing in philosophy and in their purpose. One places her unerring faith in God. The other, places her unerring faith in herself.

Themes flip between the role of God, the role of architecture (and art), the role of a mother, who has the right to represent a community, the effectiveness of group consultation, what is it to leave a legacy? Like a Fishbone is a series of arguments about authority and righteousness, which ultimately examines a deeper philosophical dilemma- a person’s life purpose.

It is a handsome production- set design by Jacob Nash is suitably cold and efficient, complimented beautifully by costumes designed by Bruce McNiven. And Verity Hampson’s Lighting design is subtle and effective- shifting us elegantly from the poetic to the stark throughout the course of the narrative.

An outstanding performance from Anita Hegh, as the mother gives the piece a warmth and tenderness, which could otherwise be reduced to an intellectual wrestle of righteous ideology. Hegh’s ferocity and fragility is heartbreaking – feels spontaneous and honest. It is a difficult balance to strike as the character of the mother some may find it slightly difficult to empathize with, as her ideology seems old fashioned , naive and unglamorous.

Aimee Horne’s Intern is likeable and balances the scenes with a genuine humour and an authentic spontaneity- and after a barrage of violent ideological exchanges it is the Intern’s speech which grounds us in the simplicity of what is: form follows function. Unfortunately the character of the architect (Marta Dusseldorp) is not only unlikeable, but her transition from hardnosed career woman to compassionate woman is unbelievable.

Like a Fishbone is a play that get’s caught in your throat. Like that of a soft fleshed fish- the translucent , invisible bones of the play are hidden. And before you can fully comprehend what is happening- that which was intended to be a source of nourishment, is now that which is the cause of your demise. Anthony Weigh’s play itself, is largely about the structures – the philosophical structures – which shape us and our world- that frame our perspective. Tim Maddock deftly handles a very intense argument with great skill and finesse.

Like a Fishbone is a wrestle which is personal, and unresolvable and the sport can be best be found not in the end of the play- but in the discussions in the foyer after the show.

Just knocking off some other work and then I will write a review of this play too – WITH – Bang. The two together in an interesting ‘compare & contrast’ way….

Thanks Gus for another huge slab of passionate thought and thoughtful passion about those little Aussie plays you so love and care about. As opposed to the big American ones that I just adore – lol…

From the reviews I’ve read the moral conflict at the heart of this play seems a strange one for an Australian playwright. As far as I know we’ve never had a high school massacre, nor a controversy over a memorial for anything in the slightest way similar (Port Arthur or Snowtown at a stretch.) Interesting though that the many known sites of indigenous massacres are never considered for such things though – maybe that would have been a more culturally relevant path to go down than the predictable ‘War On Tourism’ road (or whatever it’s called these days). As an Israeli I was talking to recently pointed out to me – Australians almost seem to wish such ‘world class’ tragedies upon themselves with concerns which to a native of Tel Aviv look ridiculous (removing garbage bins from rail stations, etcetera.) As she said – “in Israel if you want to cause panic just leave a box in the middle of the road,” as there people know it means something real, threat wise. Anyway, I didn’t see the show, so what would I know?

PS: don’t ever be shy in asking moi along Augusta if you’re short of a +1!