Jack Charles V The Crown | Belvoir

- April 8th, 2011

- Posted in Reviews & Responses

- Write comment

Try as we might, there is no escaping history. We carry it in our bones, our skin – the wrinkles, freckles, scars carry the impact of a life lived – a life of suffering, struggle that no one can avoid. This tender organ – the largest in our body – constantly shedding, in minute scales – contains our unique genetic information which we leave as a trail where ever we go – like Hansel and Gretel’s bread crumbs. Our organs contained within, our silhouettes are defined by our skin – the edge of the outside world touches us through it – and we, touch the world.

It seems a strange way to start a response to a play – but really there is a lot to talk about – and there is much I could talk about, were we at dinner – or even in a foyer. But here, online, I am only going to add small thoughts to this conversation that have already been well covered by others:

James Waites – always the top of my favourites lending his personal perspective and history to the discussion – if you don’t read him, you should… http://jameswaites.ilatech.org/?p=6583, Diana Simmonds my favourite official onliner who gives eloquent free-flowing reportage here http://www.stagenoise.com/reviewsdisplay.php?id=526 and of course the king of print Jason Blake http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/theatre/voice-of-experience-softens-the-edges-of-a-life-lived-rough-and-hard-20110403-1ct35.html…

It cannot be said enough how important it is to have a diverse representation of voices on stage. Of backgrounds, experience, of gender, race and ethnicity. Belvoir has a long tradition of seeking out and nurturing voices of indigenous theatre makers – and the alumni are impressive high-caliber artists. I still have Wayne Blair’s Conversations with the Dead ringing in my cells long after the event. Long after the event.

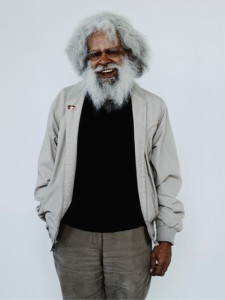

Here in 2011, we have in Jack Charles V the Crown – a story that is sadly unsurprising – a story of an indigenous man’s rise, fall and rise in white society. A story of abduction, addiction, incarceration, celebrity -everything a modern magazine would advertise of an American starlet’s claims to fame. A story (for those who saw Amiel Courtin-Wilson’s documentary film, Bastardy) that is a theatrical sequel – Jack Charles’ second coming, so to speak. And it is remarkable to be taken on that journey of dark and grubby Melbourne backstreets in the white lit landscape of a Sydney theatre. We are seeing, in the mere fact he is present – a story of hope, survival (of redemption). We watch as the history of this man is explained – enacted, projected, sung. A long confessional interspersed with song and story – a pastiche of experience co-written by Jack Charles and John Romeril and directed by Rachel Maza Long.

The personal part of this response comes from the skin that I have – my white-appearance skin – my skin that holds many lessons learned – and comes from a diverse array of backgrounds – mostly Celtic convicts, farmers, thieves, righteous tee-totaling country women, and (now recently discovered) indigenous Australians. My ancestry, like many Australians, is mottled with dark and light – my identity difficult and displaced. And it is my own. I have always held the view that we are all three bad choices away from being amongst the unfortunates – and perhaps that is why I talk to beggars, why I’ve worked in soup kitchens and for charities – why I refuse to look away or ignore those around me.

And there is a lot that I have questions about – questions that are not there to be didactic or to provoke or scold – these aren’t questions which are crafted out of an agenda. I start thinking about the future of indigenous theatre… I think about the absence of indigenous punters – in all theatres, and on the night that I attended. I wonder if this a black story for a white audience? Where is the indigenous community that live in the surrounds of the Belvoir building – what would seeing this mean to them – to those who have lived moments of a parallel life with Jack – what would it mean for a young indigenous man to hear this story from an elder – to grow strong and determined – to be empowered to be reassured? What does this play do if it merely preaches to the converted? What is the function of this type of theatre – is it to reassure the audience? Are they hopeful? Are they righteous? Are they saddened by Jack Charles’s experience of being trapped in society of white law – but delighted that he has over come it? Are we self-loathing as the audience who would turn on this man if it were our GUCCI glasses, motorola phone he had stolen – or does this offer us the possibility of compassion and understanding – will his story flash upon our inward eye? Will be make small efforts to understand and reconcile – which is sometimes hard to do in this meritocracy we live in.

How will this change or affirm us and our beliefs?

One thing is certain- Jack Charles is a remarkable performer, if for nothing else his stamina and breadth of bravery. Essentially this is what the story, his story is – it is a story of courage and bravery – and the act of appearing on stage, confessing and confronting the past is a tremendous thing. Which is triple what any of us, with comfortable lives, and theatre subscriptions, and well appointed furniture can even begin to imagine. He has lived it large and tough and on the edge – and in spite of it all, he continues in his skin- the skin that has seen so much, and kept so much within it.

My wish is that the stories continue to come – stories that are diverse in flavour and message and genre – stories that are from all people – of all ages- that we continue to learn and find compassion, understanding, bravery and inspiration from each other.