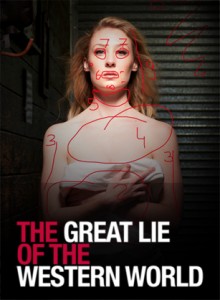

The Great Lie of the Western World | Cathode Ray at The Tap Gallery

- April 25th, 2012

- Posted in Reviews & Responses

- Write comment

“Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. One man thinks himself the master of others, but remains more of a slave than they are.” – Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The Social Contract by Rousseau is probably one of my favourite philosophical works. At 17 I carried a battered copy under my arm, whilst I ran to my philosophy lectures at Sydney Uni (often in my flannelette pyjamas and over coat…) It explores the evolution of our lives into what we refer to as “society” – we enter into an agreement – that to enjoy the safety and prospertity that participating in society, we forego our natural/primitive instinctual state and submit to law. Rousseau also talks about how these laws are created – who decides them, bearing in mind, of course that (wo)Man is instinctively selfish and operates within self interest.

Published in the late 1700s, there is something about Rousseau that ressonates more than ever. The western world – sometimes known as the “free world” is anything but free. Suffocated with choice? Perhaps bound by social obligation? Perhaps strangled by the myth of independence?

The Great Lie of the Western World is an interesting night at the theatre – both in content and in form. And I enjoyed many things about my night at the theatre, the night I attended. I think the ideas were really timely, I also love the sense of place and location within the writing. I like the age of the characters.

Not often do we see plays of this (broadly speaking – A classical structure where the protagonist is visited by an “outsider,” has personal (internal) struggles to overcome, a truth is revealed and a choice needs to be made.) traditional structure and duration in independent theatres. Perhaps the rise of the Fringe Festival with it’s portable opportunity has scaled-down or limited most playwrights to placing their writing in a 60 minute duration? Not so with The Great Lie of the Western World.

I have not read the script – nor have I come across Alistair Powning or Michael Booth’s writing previously – so much of my reaction to the texture of the work is based on performance.

What is interesting about the structure of the work is how much the writing varies between characters. Most notably the style of delivery between the two male characters, Simon (Powning) and Emerson (Both) is casual and seemingly spontaneous – with the same invisible inkmarks like that of a Woody Allen film (that is, when Woody Allen is playing himself or perhaps in a similar flavour of Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm.)

At times the “realness” of the delivery is as spontaneous and real (or not) as reality TV. The female characters, Paige and Fiona (Jessica Donoghue and Kate Skinner respectively) however are highly structured and delivered in a tradional naturalistic style. Powning and Booth may have more liscence as the writers – but the style suggests improvisation – though I have been assured it’s not – think Belvoir/Malthouse’ Thyestes without the adaptation backbone.

What is gained is a sense of voyeurism. What is lost is clarity of delivery. But this is only for the male characters – is this a gendered choice for the sake of the story? A choice indicating something of the characters? Are the men lost? Have the female characters got their lives more “together” hence why they don’t fumble and bumble their way through a conversation? Or is this a case of the writers taking licence?

Within the content we see lives in crisis – exhausted, lost, lying, distrusting. We hear the philosophical musings of Emerson, who walks the earth…

Fiona and Simon are both trapped within their own decisions, life choices and life-style and life expectation (wealth, marriage, relationships). Emerson actively challenges these beliefs and constructs. Paige tempts both with an alternative. Both antagonise the protagonists.

However – all these challenges remain a fantasy as the ultimate result do not really reach the characters enough for them to make a significant change. The ideas float and remain on the surface, not under the skin- as Fiona decides to stand by her man. When really, more than anyone, she needs emancipation from her duty, her nurturer role, her self-limitations. And for me, the end of the play tells us that love strangles and shackles us to struggle. A tragedy.

There is no doubt that much about our contemporary lives is in crisis – and The Great Lie Of The Western World is a portrait of that crisis, but offers no definitive message, nor suggests a way out or way forward. Should it? I don’t know. Perhaps paralysis and maintainence of that paralysed life is the point?

As a piece of theatre, though I am in favour of innovative experiments with form and style, I think any production interested in cimmunicating with an audience should practice that communication with a director. Clarity, sight lines, lighting choices, design choices seemed sacrificed for the auteur control of the writer/performers. I think if this work aims at reaching beyond an intimate venue like The tap gallery (with a maximum of 45 at a time) either Cathode Ray Tube must honour its name and dive into small screen (or big screen) production, OR start reaching out to like minded artists who are passionate about their vision for contemporary, devised script writing, and nuanced invisible acting. But, as it is, I think the start of something very evocative is there – but needs more support to reach the audience it deserves.

Read more from Kevin Jackson: http://kjtheatrereviews.blogspot.com.au/2012/04/great-lie-of-western-world.html

OR

Jason Blake: http://eightnightsaweek.blogspot.com.au/2012/04/review-great-lie-of-western-world.html#!/2012/04/review-great-lie-of-western-world.html