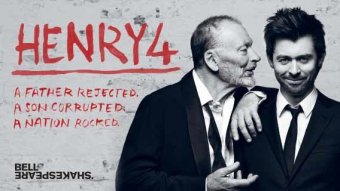

Henry 4 | Bell Shakespeare

- June 16th, 2013

- Posted in Reviews & Responses

- Write comment

The show may have closed, the milkcrate set may have been dismantled and re-distributed, the actors return to their own voices and thoughts and their daily clothes – but I’ve still been digesting the recent Bell Shakespeare production of Henry 4.

Catching up so late on my writing and thinking about productions, is a curse and a blessing – and a priviledge. In 2007 (when I began writing reviews for Australianstage) I would write and launch a review within 3 hours of seeing the show. This has its benefits and its drawbacks: the memory is fresh, the impression still present, but like trying to understand a landscape painting by pressing one’s nose up against the paint, you may not often see the whole vista. Perhaps I’m just trying to console myself for an egregious lapse of time. Or perhaps I am justified.

Personally, I don’t favour reviews that cherry pick actors to be elevated and spotlit. I also don’t really find that style of engagement with a work particularly revealing nor revolutionary: after all why would we need to be told that as an audience, we can spot that ourselves. And the merit of acting is as personal and taste based as any artistic preference. I’ve chosen not to give knee-jerk praise nor a boot in the dramaturgical backside (Please read Cameron Woodhead HERE).

This response might address some ideas surrounding anarchy, power and manhood within the context of art, and the wider context of Australian society.

But really I want to talk punk.

Let’s look at Bell’s aspirations of Henry 4:

And some months later once the generic notions of “theatricality” have susbided: the trailer:

“Not a polished evening but I hope a kind of rough and spontaneous evening in the theatre, so I’m starting discussions with my designer Damien Ryan my other director and as to how we can acheive this sense of anarchy and wildness and still give it a big shape so its totally in control in terms of how we’re going to manage it, but how do we make the audience feels its a totally spontaneous event.”

And so, we have a very basic presentation of anarchy:

Wikipedia says of punk: “The punk subculture… is largely characterized by anti-establishment views and the promotion of individual freedom… Jon Savage has described the subculture as a “bricolage” of almost every previous youth culture in the Western world since World War II, “stuck together with safety pins.””

There is nothing so far away from “punk” and “anarchic” as Bell Shakespeare: a company which has enjoyed huge success off the established curriculum of high schools mandating Shakespeare for students (what I might refer to as bread and butter audiences), and also perpetuating a very traditional (contemporary) theatre venue tradition of “the audience sits in the dark watching actors in the light” (interestingly not the tradition the plays were written in), and the highly formal and structured hierarchy of the company behaves as a corporate business must. All of this of course creates an environment of controlled and measured, skilled and scholarly art-making.

(Hm. “Scholarly art-making.”)

Bell Shakespeare is all about the establishment. Bell Shakespeare IS the establishment. And this is what I find so strange about this reading of Prince Hal and the politics of the play. Especially considering from up top of the play Hal admits that he’s soon going to “grow up” and join the ranks of this family.

The mechanical world of Bell Shakespeare’s productions are far, far away from any anti-establishment rebelliousness. Productions are by and large traditional re-imaginings of the text – over-layed with modernised costuming and designs (some heavier than others): and Bell admits that in his opening trailer: to give the appearance of anarchy whilst it all being controlled.

In essence all performance and theatre (from all companies) should aim for that level of energy and sleight of hand. Does it succeed?

What would happen if the audience wasn’t sure that it was controlled: what if the structure was broken open and compromised: what if there was real and true possibility that it could all fall apart?

What if the actors were improvising?

What if there was no script or no rehearsal?

What if the audience interacted with the performance?

Would that be anarchy?

I felt that at moments there was a small fizz of anarchy with the Schaubühne Hamlet (Sydney Festival 2010)

We can’t help but being completely aware of all the layers of establishment that go into theatre making: the reverence of a single director (BELL) and a single playwright (SHAKESPEARE) echoes the empire of the historical plays they stage. The next generation of Shakespearean enthusiasm, Sport For Jove started out operating as an Independent company (a little closer to punk) – and now Damien Ryan joins Bell in directing Henry 4. Theatre in its very structure is an establishment, a tradition, a mechanism of agreed status interplays.

Let’s look at punk ideologies: “Although punks are frequently categorised as having left-wing or progressive views, punk politics cover the entire political spectrum. Punk-related ideologies are mostly concerned with individual freedom and anti-establishment views. Common punk viewpoints include anti-authoritarianism, a DIY ethic, non-conformity, direct action and not selling out. Other notable trends in punk politics include nihilism, rebellion, anarchism, individualism, socialism, anti-militarism, anti-capitalism, anti-racism, anti-sexism, anti-nationalism, anti-homophobia, environmentalism, vegetarianism, veganism and animal rights.”

None of this is really relevant to the production which nodded at the fashion and the music and the notion of the “outsider” – but without any depth or relevance to the play itself.

What was understood however is the issues that surround “integrity” – which is the hallmark of maturity.

Henry 4 is a coming of age play about understanding one’s integrity – and that is not something which is mutually exclusive in the realm of the punk or alternative subcultures. Such a reading reveals a lack of compassion and understanding of the need for and position of subcultures in society. Subcultures have a huge amount of integrity seeing capitalism as a “sell out” – and this is why this conceit did not at all work for me in relationship to the character’s ideology

Prince Hal (in the view of a punk sensibility) sells out.

Falstaff is a sell out (a delusional one at that)

The only person who honestly knows who he is and is honest (about his actions and limitations) is the King.

What seems to be adopted and stretched over this play from the idea of “alternative” or a “punk sensibility” is the music – which is energetic and gritty (though still performed with a measured and controlled obedience in a very obedient context.)

The punk movement is perpetually interesting for younger generations as it taps into natural need of all humans to establish their identity through pushing away from certain cultures and running towards others. It asks us to identify and question what is, what we’ve inherited as culture and law and aesthetic – and asks us to step up and make ourselves anew.

Unfortunately this idea isn’t quite linked in with this story, nor this art form itself, nor this particular company. But the rebellion (which has now been normalised) is the irreverence to the playwright and the text. The rebellion/anarchy is happening in a co-vert way: Bell is simultaneously revering and smashing up the idea of Shakespeare’s authorial intent. The fact is many of Shakespeare’s texts are smashed up versions of folios and quartos. There was a high tradition of improvisation in Shakespeares performances – the audiences demanding more, shouting out, eating oranges and getting tangled up with prostitutes in the muddy pit of the audience stalls: There can be no reverence to something so fluid. Shakespeare was irreverent and his audience anarchic by today’s audience going standards.

OK. Not much left to say except:

I really liked the music.

And now, for some TOTALLY UNICORN… read more about them HERE

Just a quick one, Damien came from Bell and has worked with the company all the way through his establishment of Sport for Jove rather than vice versa. My adoration for SfJ is in the wonderful visualisation and truthful honouring of the text. May not be punk renditions – to quote old Will “But what of that”?

I saw Othello this week, & was once again blown away by SfJ’s work (most particularly Damien Ryan as Iago). Worth seeing even though I know Shakespeare is not your highest priority!