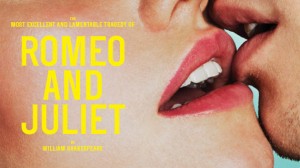

Romeo & Juliet | Sydney Theatre Company

- November 18th, 2013

- Posted in Reviews & Responses

- Write comment

Romeo and Juliet – you know the blurb “The greatest love story of all time? Certainly. But it’s also a prototype for some of culture’s other great narratives: the rebellion against generations past, and the need to escape from a predetermined future. One of the most thrilling things about young love is that often it is forbidden. And that very act of prohibition makes it all the more alluring.”

And so when we know the story so well – the star crossed lovers who end up destroying their lives (and the lives of those around them) – that in the production it becomes more about the journey than the destination.

Here the journey is heart-thuddingly loud – but not through sexual tension or raw, urgent passion – but through the music pulsing through the speakers.

The most simple of heartbreaks can happen when one sees two people blindingly in love. It’s the stuff that keeps weddings wet-eyed. The joy of witnessing love (or lust) and the pain of remembering the disappointments love can offer – the compromises and the changes love makes in us all.

The play hangs upon the emotional temperature of the two lovers- if the temperature is tepid, the drive of the play becomes about facilitating the misguided, selfish, rebellious teenagers – not about ensuring that nothing gets in the way of true love. Perhaps this was director Kip Williams’ aim? To demonstrate the folly of young love? To show the stupidity of the friar (Mitchell Butel) and the Nurse (Julie Forsyth) in their facilitation of the union? To show the cruelty of the parents?

What I admired about the production was the comfortable, intelligent ease with which Juliet reasoned in regards to love (Eryn Jean Norvill) – she’s no giddy, silly girl, this Juliet. I also enjoyed the sweet and comfortable Benvolio ( Akos Armont – whom I fantasized was our love interest through much of this production) and the steely gaze of Anna Lise Philips as she swanned and swigged her way through a parade of feathers as Lady Capulet.

The cuts are many and varied, you can read across the reviews for responses to them:

The Australian HERE

The Daily Telegraph HERE

The Sydney Morning Herald HERE

Crikey HERE

In Kip Williams production, the drive of the play was about strategy more than sensuality. I began to realise that the truly physical embodiment of male sexuality did not sit within the bones and flesh of Romeo – but of Mercutio (Eamon Farren – humping most things and people in sight) – and that the sexual rebellion of Juliet was really an escape from a marble privileged prison (more than an internal, primal drive). These external forces impacting on the lovers thwarted any true reading of classic tragedy – as the fatal flaw within the individual which is their own undoing. As such, the production became less interpersonal and more broadly philosophical about love.

And I guess the lesson is here: Nothing undoes the power of sex like over-thinking it.