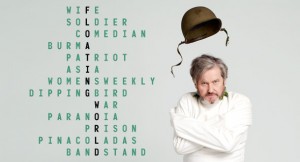

The Floating World | Griffin Theatre Company

- November 17th, 2013

- Posted in Reviews & Responses . Uncategorized

- Write comment

We owe a lot to history. The record of events or opinions that shape our opinions in overt and covert ways. Australia’s history at it’s most prideful is our participation in War – the Aussie battlers who defended the mother country and her allies against “the other.” It is the one theme in our history that is told and re-told, glorified and marks two days on the calender for rememberence. We don’t find the same pride in our settlement – how can we with the vicious murder of the indigenous Australians. We don’t find same pride in our convict heritage. But war is something different.

Sam Strong’s legacy to the current generation of theatre makers and goers was the commitment to the production of Australian “classics” – a contentious term I know – and we are still reaping the reward of this un-hip (in the face of adaptation of European classics) honouring of our local playwriting history. This is essential to understand the shoulders on which we all stand. John Romeril is one such giant. What we take for granted now in our playwriting pallet was forged in the fire of Romeril’s mind (along side that of Hewitt, White, Williamson, Lawler). Romeril gave the audience a sense of place, voice, context which was raw, sometimes embarrassing, uncompromisingly familiar and powerfully political.

In Griffin Theatre Company we see the time capsule of the Second World War cracked open. A flood of secrets unleashed upon the world in a torrent of rage. The unspeakable spoken. The horror, not the glory of war. The graphic and the gore of heroism.

A brave act for a playwright.

The essential job of the playwright.

To offer a new reading on an appearance or opinion, a politic or society, the status quo scratched until a shiny mirror shows us ourselves as we are, not as we hoped we were.

For me, I embraced this brash coloured fruit cocktail of a play with the context of my grandfather’s experience sitting in my heart. He was what he referred to as “a civilian in uniform” not a soldier – who did a lot of growing up from the farm boy from Bega to the returned solider… my grandmother smoothing his heart and voice when it erupted in sadness or fear (behind closed doors). He was full of a strong of the same stories – a glorious portrait of war , which only revealed its true face when I was in my university years – the content not really appropriate for a child. The responsibility of resulting actions of an individual haunted him. He compensated where he could. But like all men battling the expectation of what makes a hero or a leader or someone strong, the battle wearied him.

We are entering a time when the new war heroes of Afghanistan will return – and we need to be prepared for the resulting societal tremors from that quake. And The Floating World reminds us of the limits to our own denial.

Sam Strong lead a bright and bolshy brigade of performers – Valerie Bader, Peter Kowitz, Tony Llewellyn-Jones, Justin Smith, Justin Stewart Cotta and Shingo Usami in a beautifully glitzy glamourous clash of design by Stephen Curtis. The play glides along weaving and layering – resulting in that huge and necessary unfurling of words from Les.

Another thing to note – that structurally, should this play had been written now – with the jokes and the language and the structure it has – I wonder if it would have make it through the scalpel-wielding script assessors of the Australian play development mafia? (which I suppose, I am one) Would this wild and layered essential play found its feet if the formula had been enforced at Melbourne’s Pram Factory? I wonder…