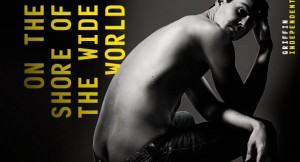

On the Shore of the Wide World | Pantsguys and Griffin Independent

- January 25th, 2014

- Posted in Reviews & Responses

- Write comment

Swathes of heavy cloth, canvas, or calico – the thick sails of a ship or the drop sheets in a house mid-renovation. Scuffed grey floor. Some chairs. Functional, nearly sculptural. A neutral zone for the scenes to smear and blend, I’ll know where I am because I’ll be shown or told through light or line or a hum of sound.

Human relationships are amongst the most intriguing examples of symbiosis. Sometimes a mutualism, sometimes commensalism, some times parasitism, humans just can’t seem to live without each other. At the very core or the start of this is the family. There’s no doubt families are difficult, essential, destructive, nurturing, loving, confronting, fascinating building blocks of any community. Family – the idea of, the actuality of – is inescapable. And the inherent conflict is this: the battle between the self/self-interest and the family unit/community interest.

The battle with oneself is hard enough, but to battle with oneself in the inescapable presence of family – the memory of, the reality of it, the expectation of it? The assumptions. The history. Generations colliding and asserting a world view which is nearly incomprehensible to the other. A negotiation between duty to self and duty to others is endless – and more pointed, more poignant in reference to those whom on we rely on, owe much to – family.

In a continuation of the Pantsguys juggernaut, On the Shore of the Wide World (the second play staged by this company written by Simon Stephens) has harnessed once again the impeccable Anthony Skuse, whose direction – firm, kind and clear – releases more than one would assume from this play. On face value the dialogue is fairly everyday – not overly heightened – no Patrick White Dream aesthetic, no epic Dorothy Hewitt politic. This is simple, plain English.

“Alex Holmes is ready for adulthood, ready to lose his virginity and ready to leave his home town. But history isn’t on his side. Alex’s parents Peter and Alice are careening towards infidelity after the impact of a recent tragedy, and his grandparents’ relationship continues to splinter. The sting of regret is turning out to be a Holmes family keepsake.”

Essentially this is a multi-generational family drama wherein the duty to self (desire, grief, love, freedom) collides with the duty to family (monogamy, stoicism, loyalty, security). Under Skuse’s calm eye and warm heart something more is found in this beyond the narrative of pain and death and fidelity. There is a genuine even weaving of the generations pain, fear, desire is equal but different. This is a simple story, beautifully told. But this is not just a coming of age story for Alex. No. It’s really the showing of how a family comes of age. Confronts and negotiates loss and desire, faces betrayal and blame.

In the director’s note, Skuse finds a commonality in three of Stephen’s plays in place and time – Stockport over a five year period – and posits that the question hidden within this triptych is:

“How is optimism possible in a world falling a part?”

Asking this question, demands a huge amount of optimism – based on a cynical premise. It demands compassion from all – each performer and character, each audience member needs to be willing to believe in redemption or loyalty… the essence of which is love.

And in this production it’s undeniable – the answer is – has and will be – love.

Love – as a conscious decision to forgive, to choose the other over oneself, to stay, to confront what is and has been. To move over and beyond self for another – wife, brother, lover, grandparent, parent, child…

What love looks like in this family is not righteous, nor bombastic. It is the quivering, quavering, trembling stubbornness that says “no, I need you…” or “I can’t let you…”

And that is remarkable.

A strong ensemble listens to each other with intent and focus: Alex Beauman, Paul Bertram, Kate Fitzpatrick, Huw Higginson, Graeme McRae, Lily Newbury-Freeman, Emma Palmer, Amanda Stephens-Lee, Alistair Wallace, Jacob Warner.

Scenes become observed, the characters listening to the story as though they carry the memory of each other, or the concern of the other with them, theatricalizing what could be a fairly pedestrian scene of the everyday. The difference is that Stephen’s has found the tenor of three generations, the timbre of their yearning and sustained it throughout the play. It’s a beautiful portrait of inescapably inter-linked lives.

The tension within each individual – between between yearning and regret, duty to self and duty to others stretches thin. Skuse’s production like a cool Summer breeze brushes over and through Stephen’s Aeolian harp – so soft, and natural and familiar. Like breath. Like love. Like family.

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,

Before high piled books, in charact’ry,

Hold like rich garners the full-ripen’d grain;

When I behold, upon the night’s starr’d face,

Huge cloudy symbols of a high romance,

And think that I may never live to trace

Their shadows, with the magic hand of chance;

And when I feel, fair creature of an hour!

That I shall never look upon thee more,

Never have relish in the faery power

Of unreflecting love!—then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till Love and Fame to nothingness do sink.

Read Diana Simmonds HERE

Read Brad Skye HERE

Read Jason Blake HERE